Showcase of the best world wide food directors

* landing page for shots

https://shots.net/news/view/experimental-directors-foodfilm-sign-to-stink

* Link to the article

https://source.slateapp.com/director-showcase/february-2023

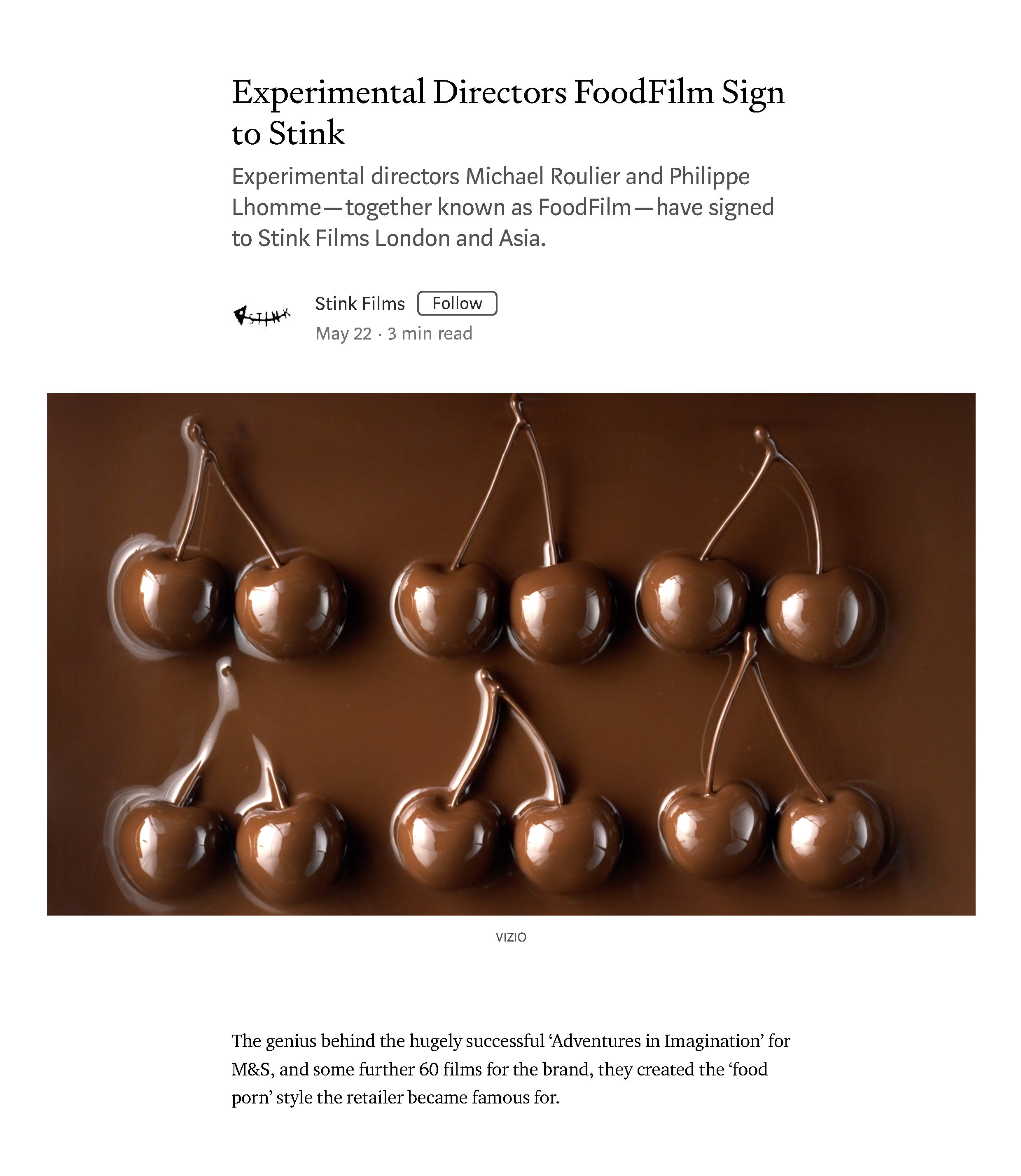

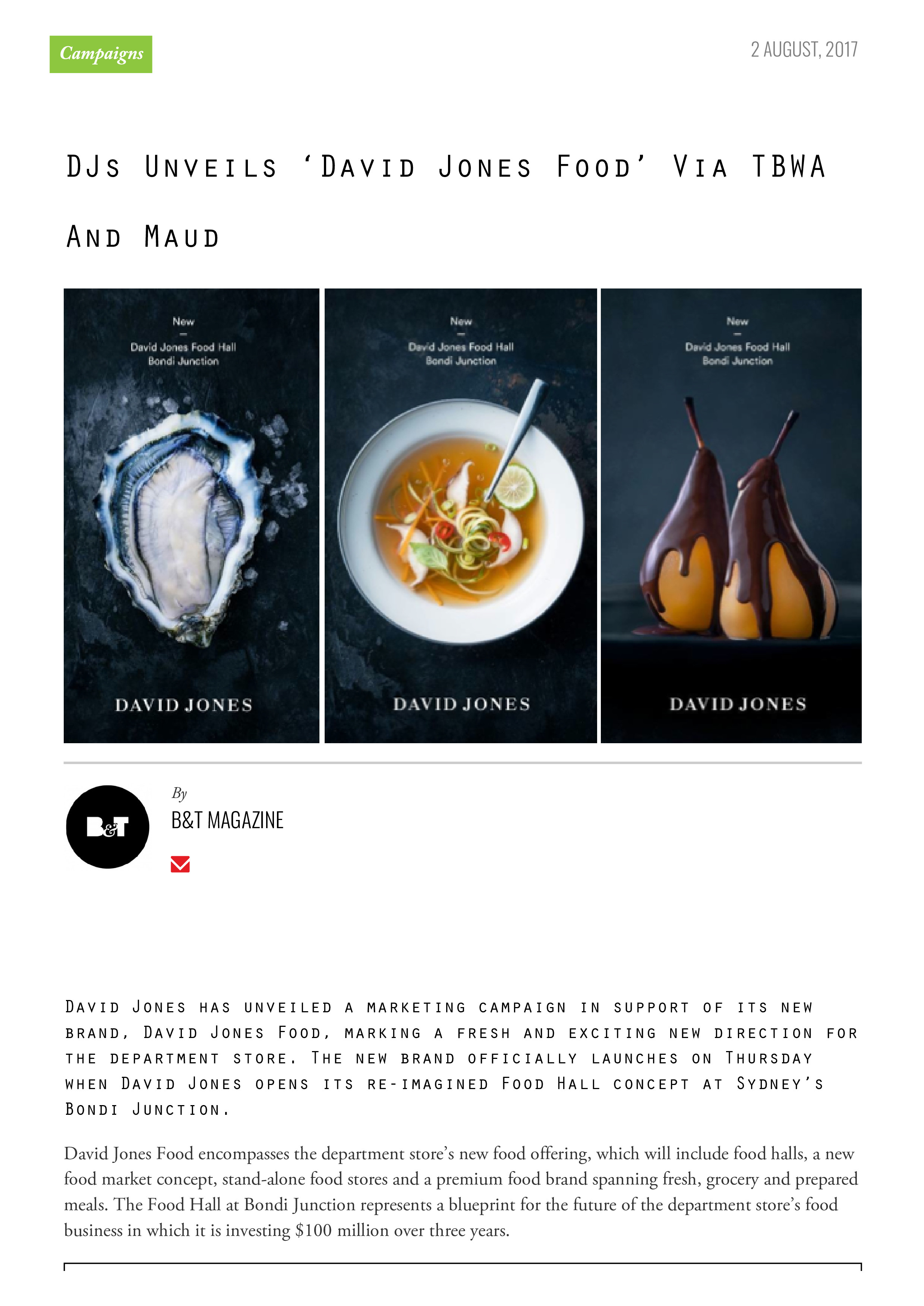

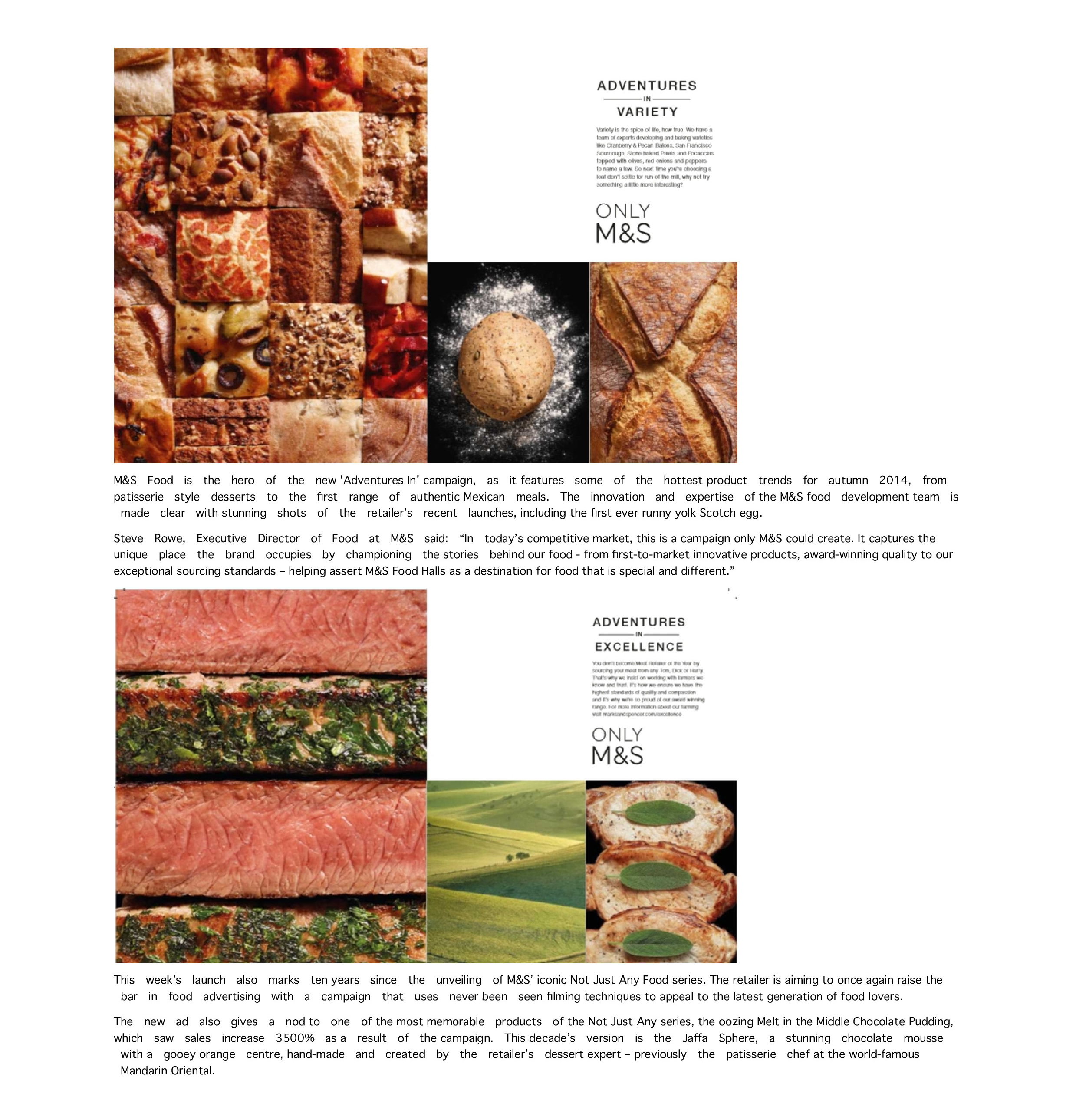

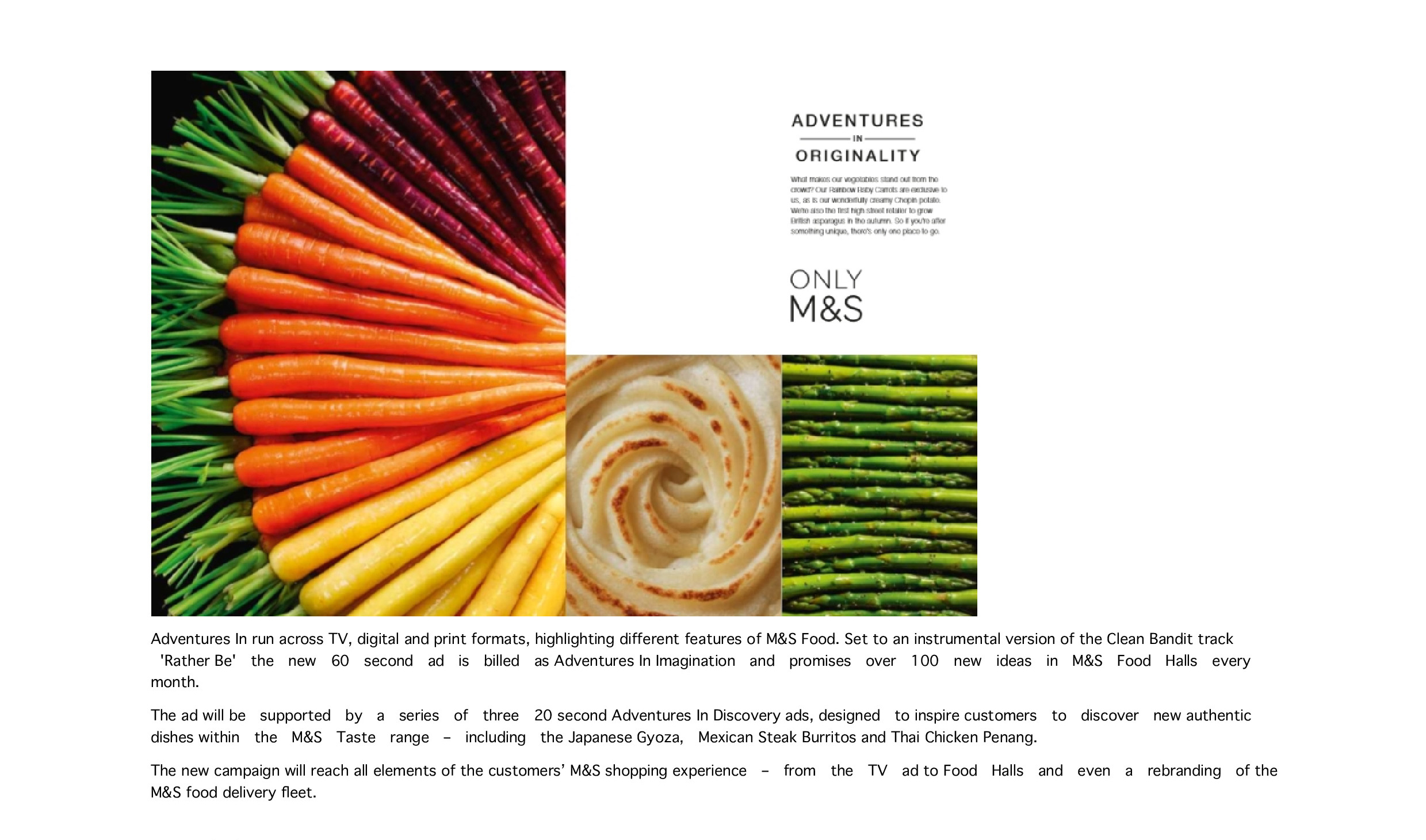

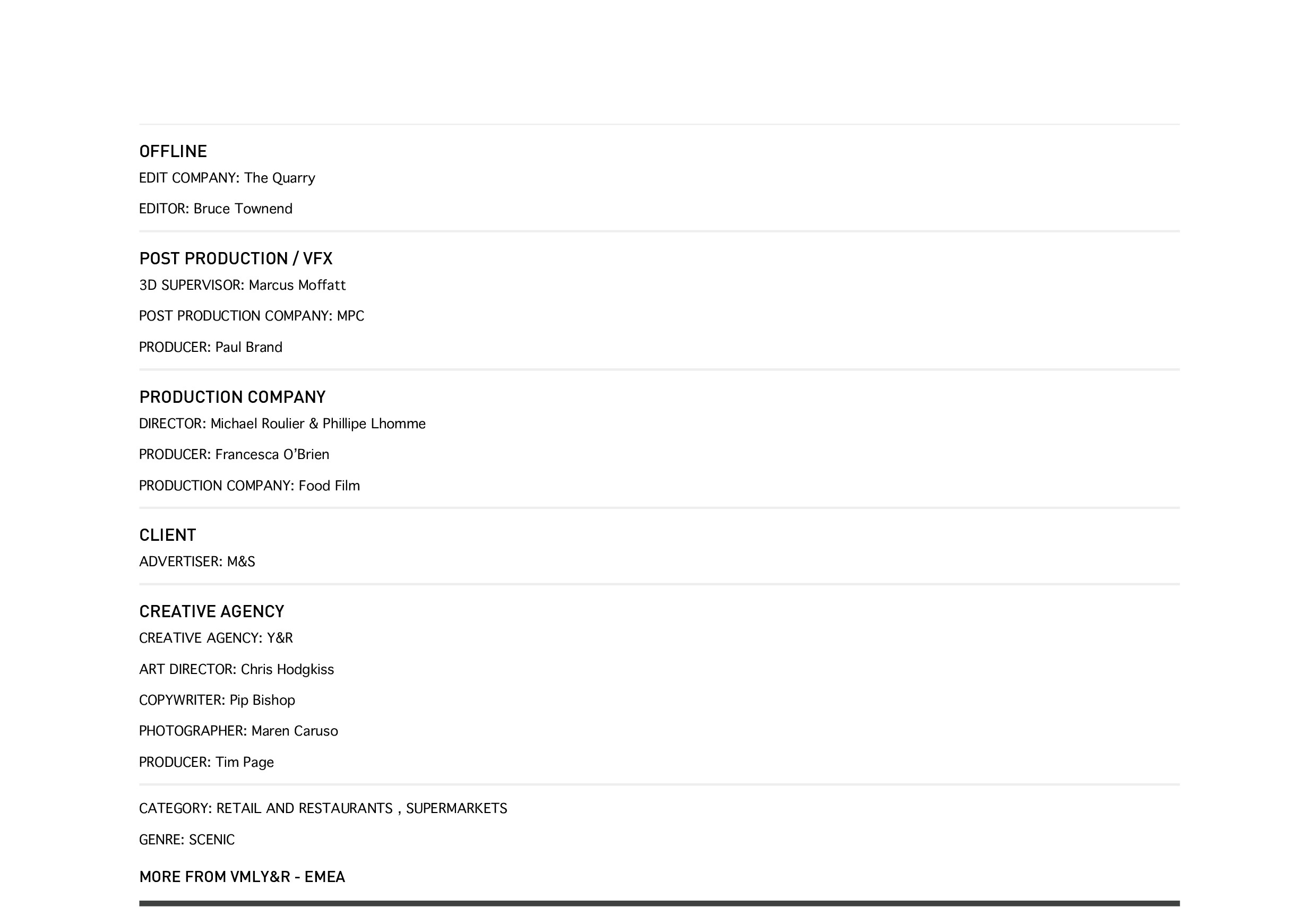

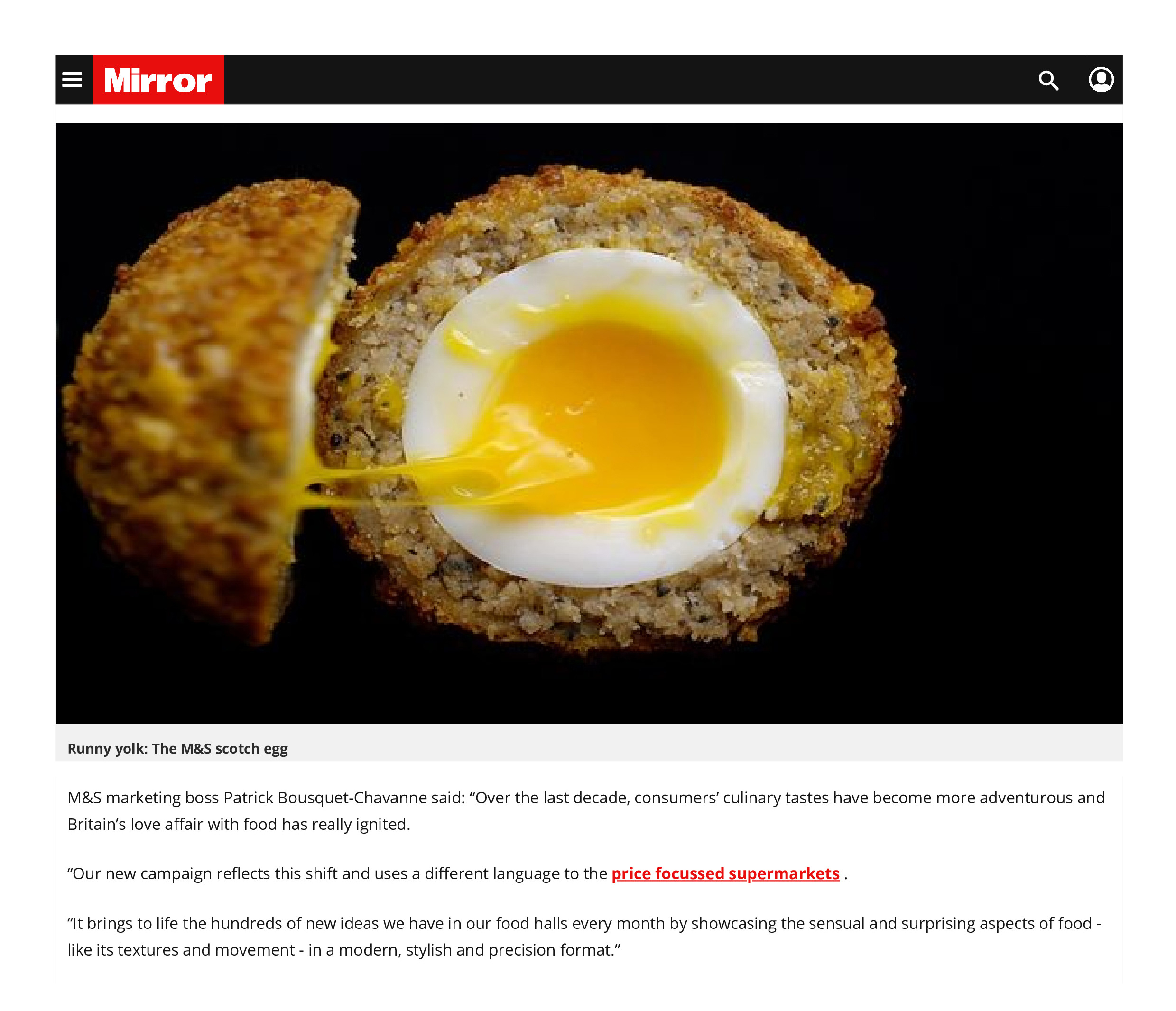

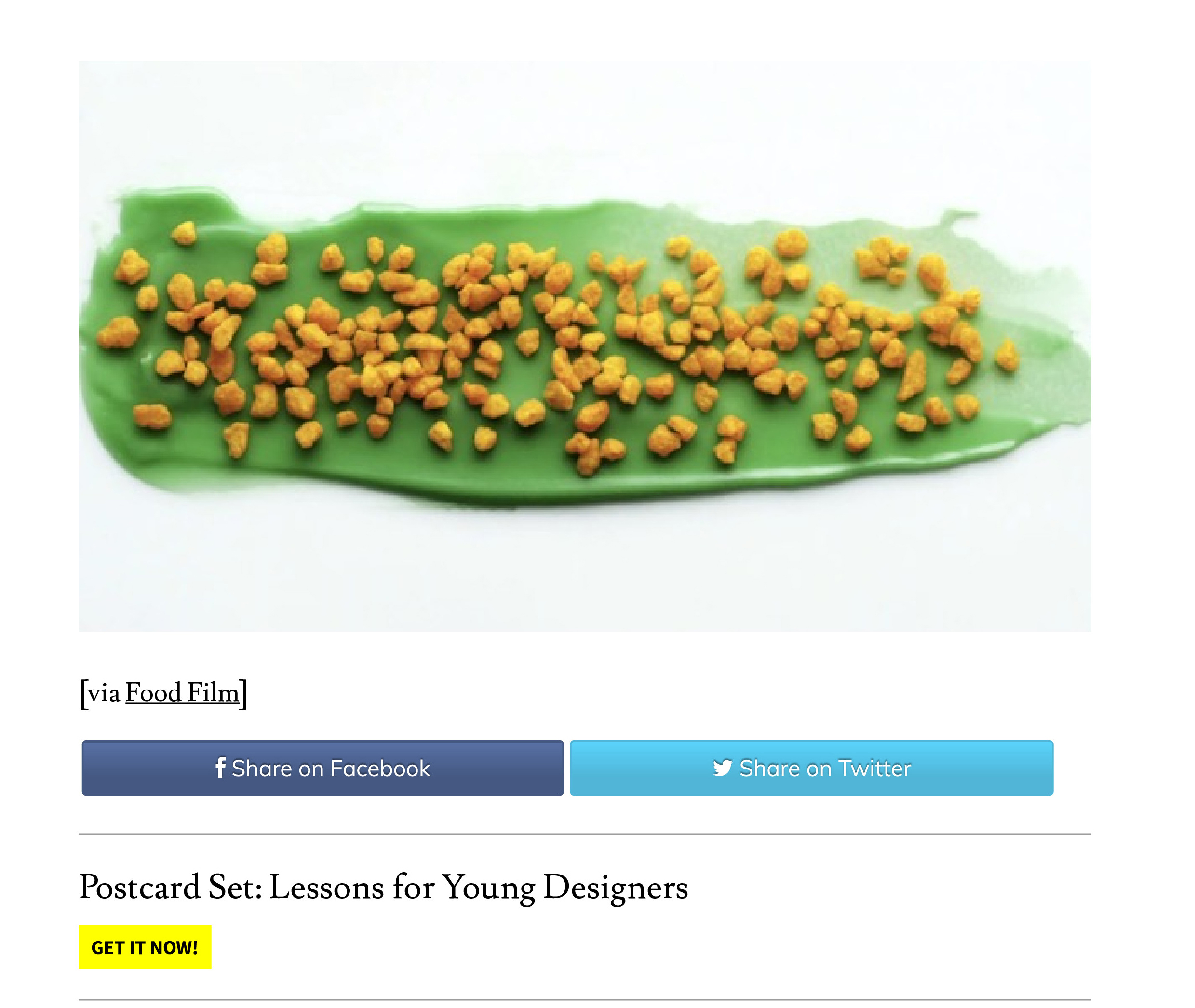

Foodfilm has perfected the recipe for artfully appetizing films.The directors Michael Roulier and Philippe Lhomme were drawn together by their mutual love of photography and culinary culture and started studio where they explore their sophisticated visual approach to food and beauty.Director and photographer Michael Roulier worked on campaigns for big brands in the luxury world before collaborating with top chefs on numerous cookbooks.Philippe Lhomme has over twenty years of agency experience as a freelance creative director.Together, they head up the brand image for the France-based food retailer Picard while directing films for major brands such as Danone, Marks & Spencer, Häagen Dazs, David Jones, Mc Donald’s, Volvic, Mövenpick, Burger King and also Yves Rocher, L’Oréal, Neutrogena, Decléor, Badoit, Milka, Kit Kat, Nestlé, Garnier etc…

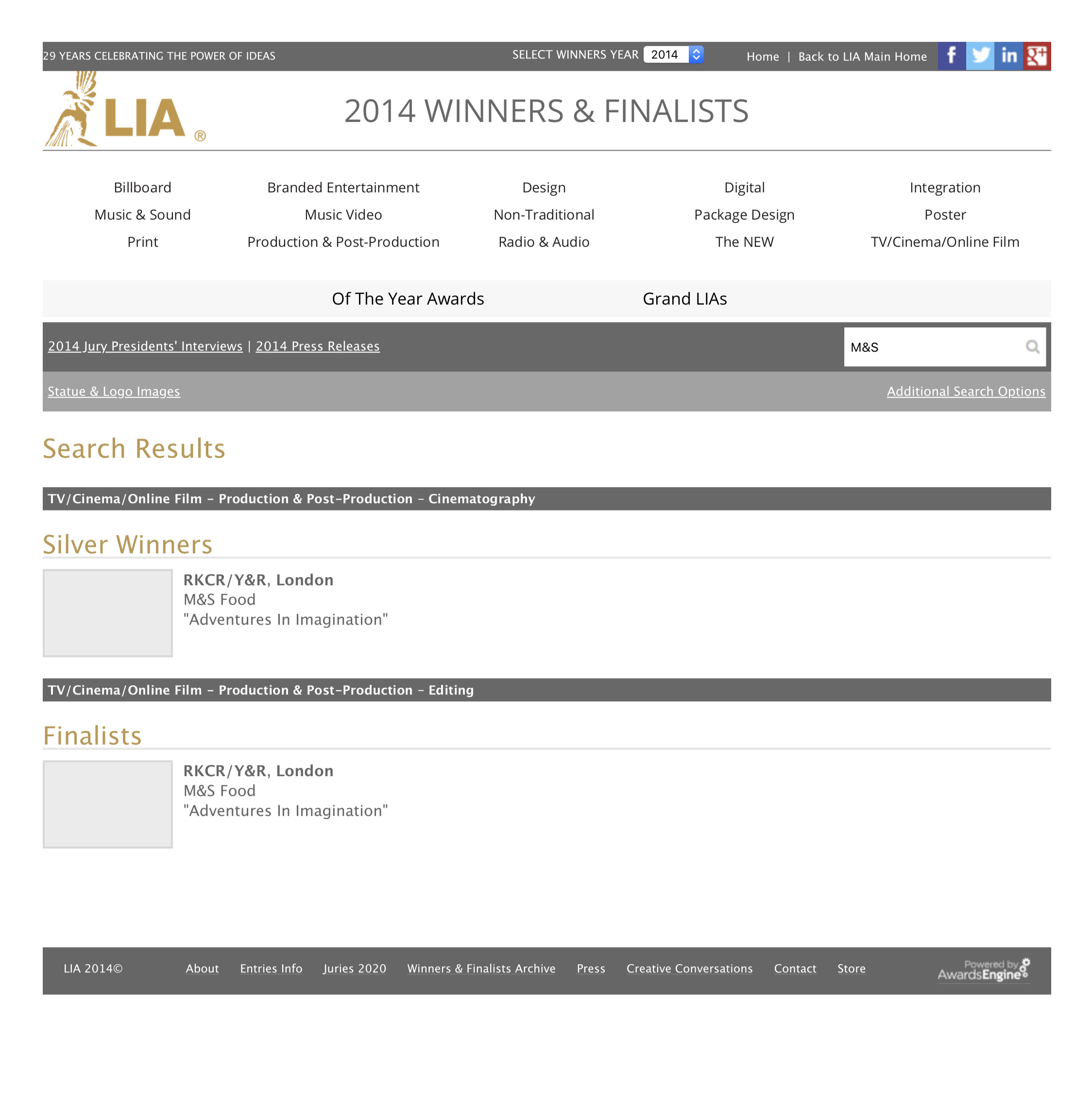

3 Nominations at the Creative Circle award 2015, won 2 Golds (best cinematography, best music) and one Silver (best editing)

Almost 4 000 000 views on YouTube !

Michael Roulier and Philippe Lhomme, Interview:

1. Could you introduce the work experience of both of you? When did you two begin to form the team to work together on creativity?

We both have quite a long advertising background, and one thing we have in common is that when we started we did not take advertisement very seriously, at least at first, being more interested into art creation.

In the nineties, if you aspired to exhibit artwork in galleries, it had to stay “secret”. So both of us entered the advertising world almost “by accident”. After finishing his studies at Penninghen art school, Philippe started painting and installed his atelier in Mesnilmontant district in Paris with no heating. Living and breathing only for his art. Still today he is the one who draws all our scripts, and it is important for us to keep it that way since it is the very first contact we have with clients to seduce them with our stories.

I take care of the writing. I started as a photographer hesitating between photo- journalism and fine arts after having passed a master in Philosophy, but absolutely passionate by all forms of photography. We where both introduced to the advertisement world almost by chance. We did not know each other at that time. It was a golden age for advertisers.Ten years later Philippe was a Creative Director at DDB mainly in charge of an iconic French award winning food brand that French people loved because of the quality of communication and visuals.

On my side I had become a studio still life photographer working mainly for luxury brands and cosmetics subjects. One day Philippe called me and asked if I was interested to do some “food tests” for the brand, and I must admit I was not too excited about it.

Food was not really glamorous in those days…it was called “alimentary photography”. Restaurant Chefs where not considered like the Rock Stars they are today, and I cared more about my personal research considering advertisement like a lovely job, but not like a finality, even though I was lucky enough to work for beautiful brands like Hermes, Gallery Lafayette etc… In the end it was a revelation. I discovered a completely new world into which I had a total creative freedom, which was not at all the case for others kind of advertised subjects. Usually Art directors had no clue about what to do with food, and it was very much ‘comedy’ orientated as they felt more confortable doing that. It was not the case of Philippe who already believed that there was a lot do in this field and really tried to bring the visuals to a very artistic level. We inspired a lot of other food brands with our images, and the brand became a real visual reference for food. Finally we ended up becoming food specialists, but it had never been our initial projects. We collaborated together for 15 years always trying to focus as much as possible on textures. Food can be naturally ugly and somehow you need quite a lot of experience to master it. We noticed at that time that the food film industry was still surfing on a quite archaic imagery, where the heroes where definitely not the food. In parallel amazing cook books where being printed as editors understood there was a huge market in selling this very artistic food approach. I did 36 books and had the chance to meet these amazing Michelin star chefs who where all desiring to do their proper “food manifesto”. It was part of their “business plan” to do such books. A necessity for them that made photographers very happy.

The brand we where working for was only doing print, but one day they asked us to film some recipes for viral videos. They where short on budget but we where given “carte blanche”. We just loved doing them, and applied our print workflow to this new experience. We where both passionate about films in our personal life. I was interested in doing experimental research around cinematic experiences inspired by people like Stan Brakhage or Maya Deren. Philippe was spending a lot of time in contemporary art galleries watching artists using video as a medium. Strangely the brand hardly used these film recipes we did for them, and it stayed completely confidential until we decided to post them all in one batch on Vimeo. It became like a tsunami: phones started ringing all the time, and many production companies scouting on Vimeo made us tons of propositions. It all went really quickly, and a year later, Philippe naturally quit his job as creative director at DDB, and on my side I switched from still-life photography to film directing.

2. Which clients do you serve currently?

Our website is built like a simple blog, so the very first page represents our actuality and the clients we lately served.

We have a lot of different clients, and we have enlarged our “film perspective” in exploring other field like the cosmetic world.

Usually cosmetic brands would hire purely still life directors specialized in jewelry, watches, or shooting very “static” items. They had a very “contemplative” approach. Almost robotic. We brought “life” and action, avoiding the 3d representations mainly used at that time. Agencies where seduced by our food background and tried to apply this “spirit” to selling cosmetics…they where seduced by our organic approach.

We love also working for cosmetic brands (L'Oréal, Garnier, Yves Rocher, Décleor, Neutrogena) because the visual grammar has to be very metaphoric, so there is a lot of creativity involved in the process, and they are really expecting this from us: “unseen ideas” to illustrate the benefit of the products…

As far as food it stays our main subjects. Our clients are very eclectic. When you shoot food films you have to collaborate with the big agri-food groups like Neslté, Lactalis, Mondelez etc…and the creative validation process tends to be quite heavy. We can vigorously defend our ideas until a certain point, but at one stage “the big machine” can easily “laminate” your creativity. We are used to that. So what’s really remains is the quality of the CRAFT. Our background in print photography really helped us here. I have always been passionate by the digital world and started working early with computers. We try to control in-house as much as we can: compositing, post production and coloring. Our workflow is very direct and since we don’t have “a complex post-production pipeline” our approach is very “boutique” in a way. We do hire some digital artists, but they come to work in our studio under our supervision before the film presentation.

We do a lot of this post production job directly on the set: we have great people around us helping us to achieve “live” what is usually done a few weeks later, which is quite an unusual workflow, and spend the nights coloring the clips to be able to show them the next day.

2bis. What’s your core concept of making creativity for clients?

What inspires us most is graphics, architecture, contemporary art, constructivism, Bauhaus, Melies (a French director of the beginning of the century creating illusion) and I am forgetting a lot of other things. Being two “brains” enlarges the perspectives and the approaches. We don’t use any DOP, so it’s really a duo work.

Philippe and I have very different personalities and skills, and strangely it works really well. But what really unifies us is a desire for elegance and fluidity. A lot of food studios sometimes lack this little something related to external input. Our respective personal passions in life keep enriching our professional work.To resume, it’s about “good taste” as we say in France.

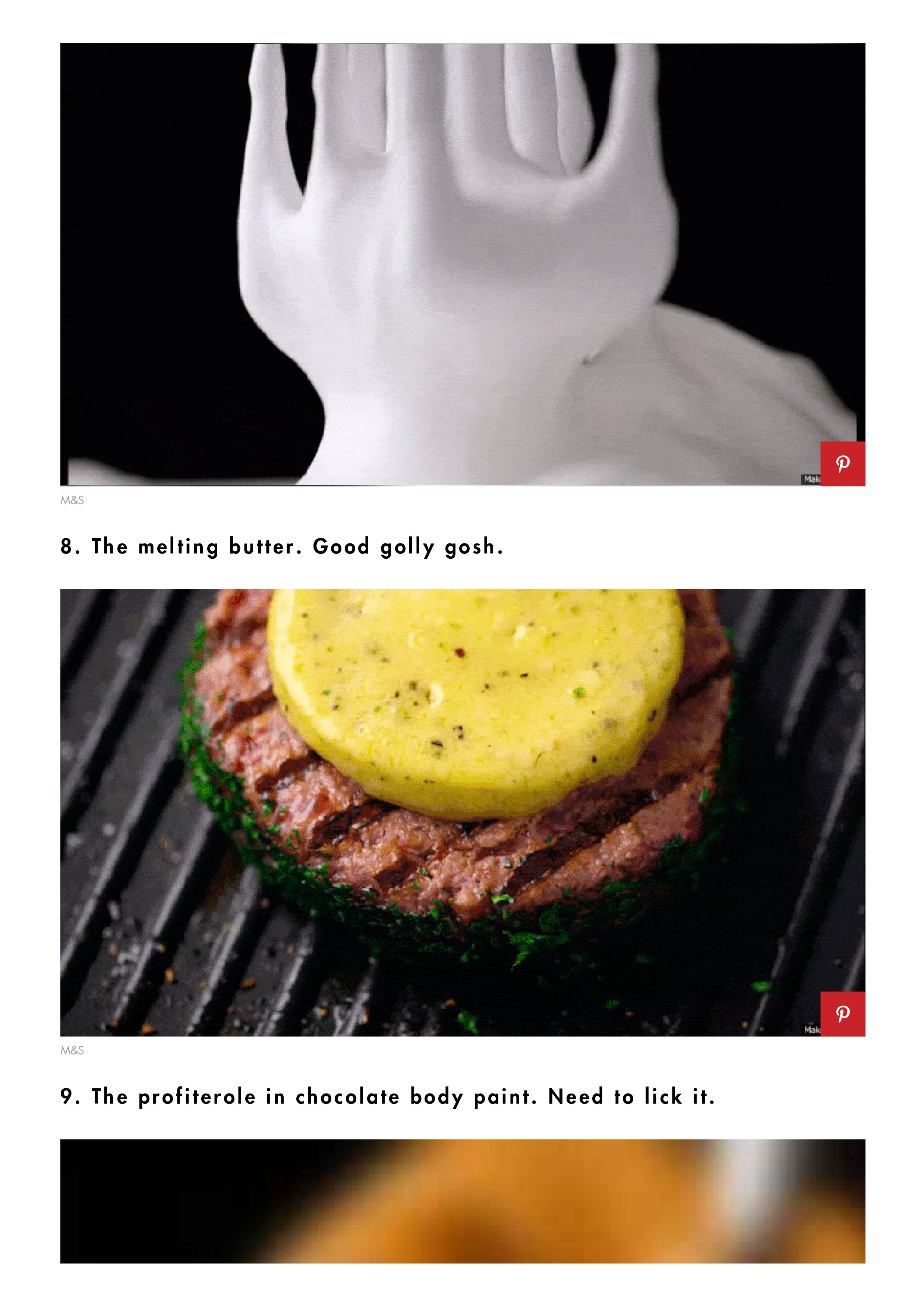

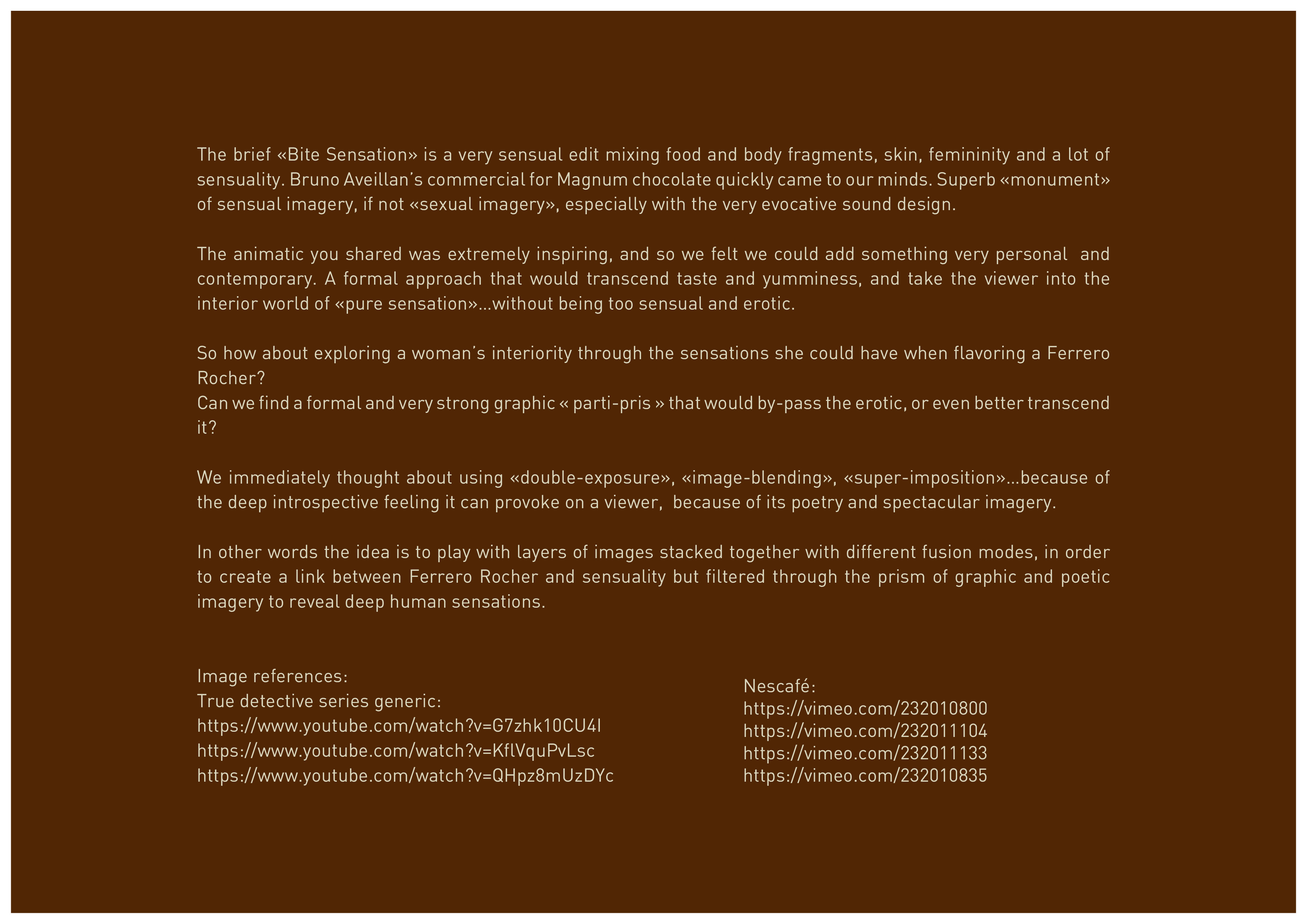

We have been too much categorized as “graphic” directors, and that saddens us a bit because we are very much about filming “sensuality”. This is probably due to our long collaboration for Marks & Spencer, and to the number of films we did for them.

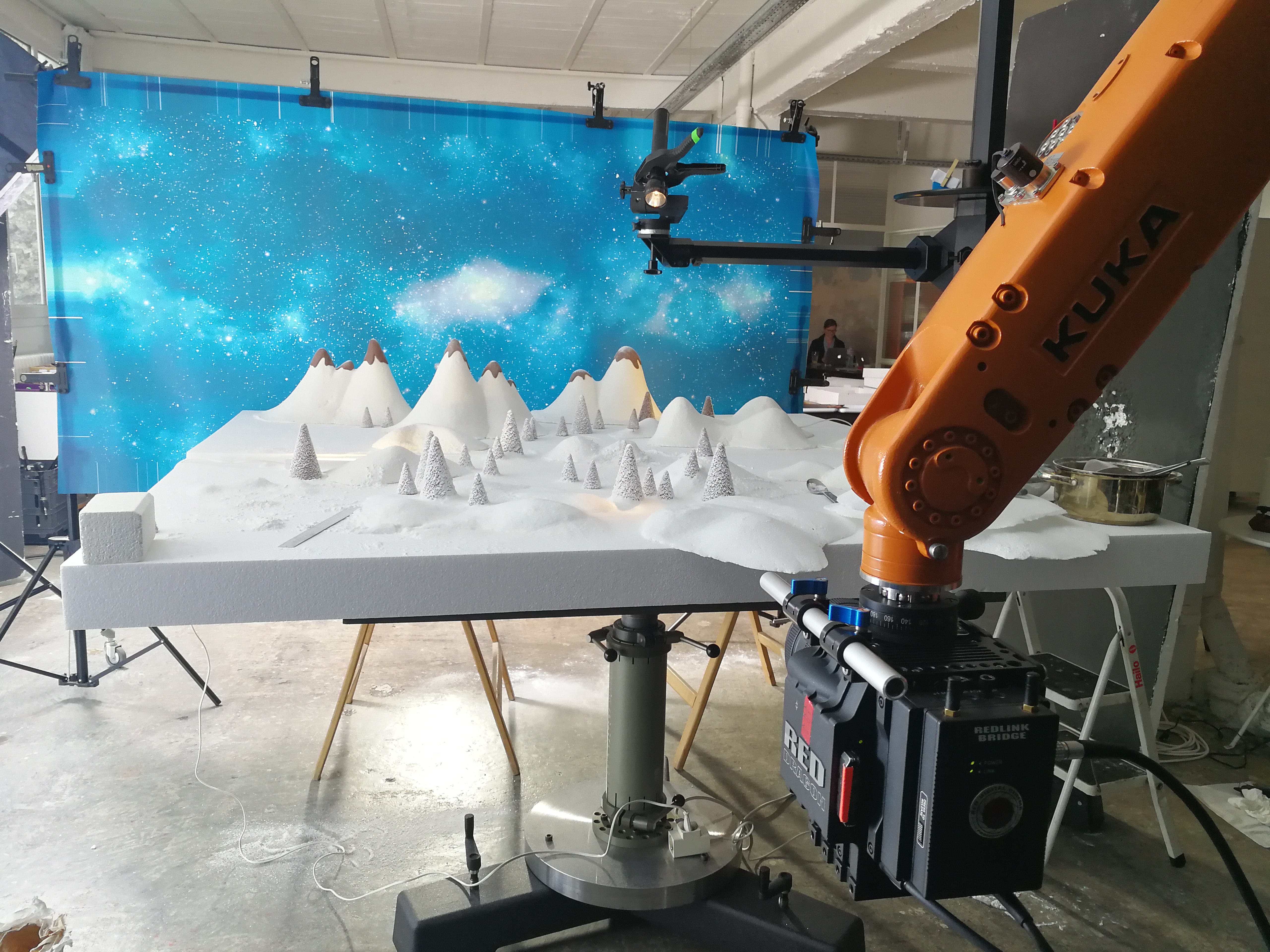

Our camera angles are usually very simple, frontal and direct. We do have an in-house Kuka robot, but actually don’t use it so much, considering that the most important part of our job is composition, more than just a robotic technical achievement.

The editing is the other part into which we have put a lot of energy. The rhythm is not only achieved by the editing skills, but also by the use of visual patterns within the individual clips. We don’t “contemplate” too much with long travellings, our work is all about action and the smart ways we have to find in order to animate our textures. And finally the transitions within clips are to our eyes as important as the clips themselves, and we always look for little tricks in order to help the editor’s work.

3. Why do you want to be specialized in food films and why began? What’s the benefits of working in this specialized area? How is this area special among creative films?

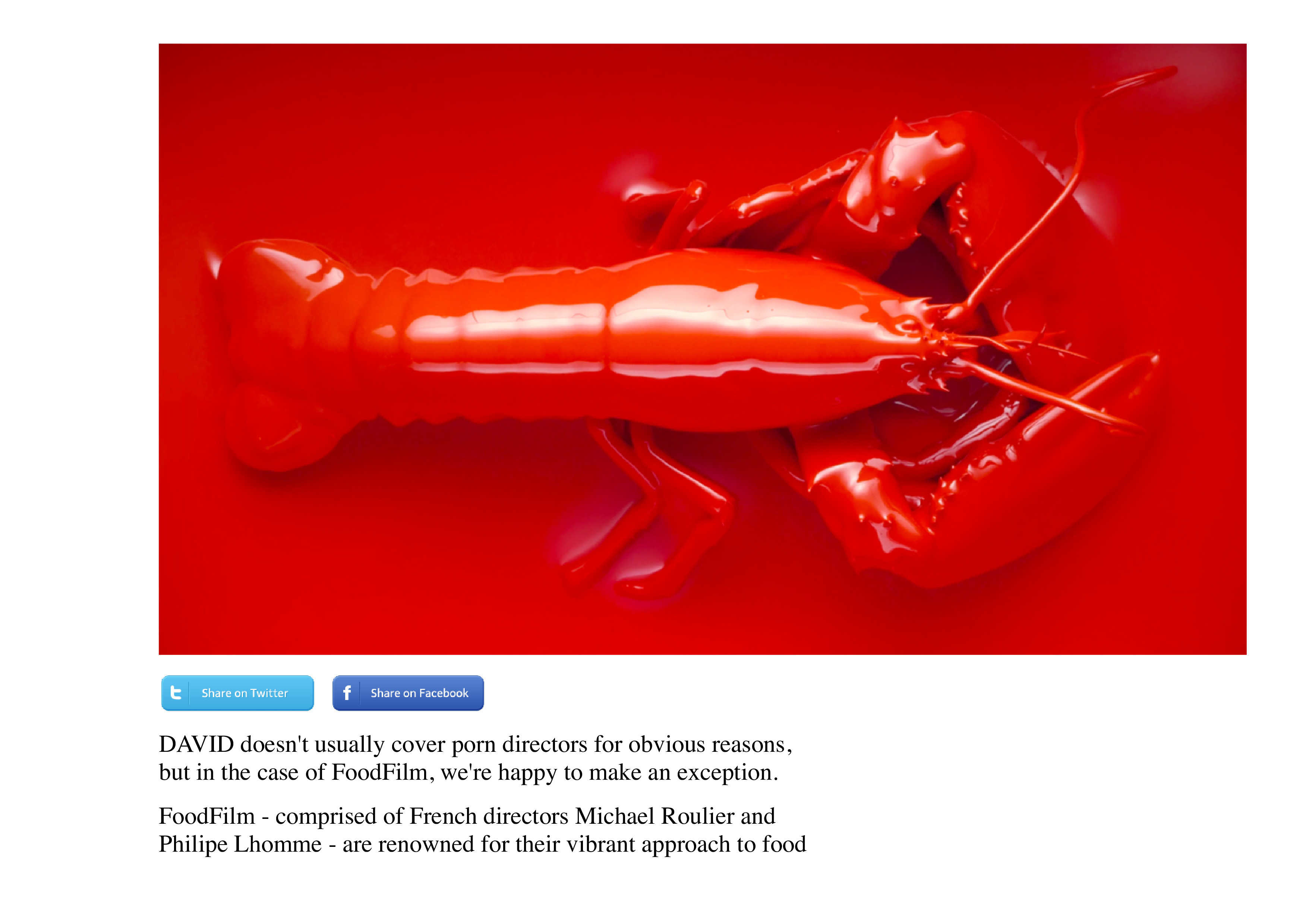

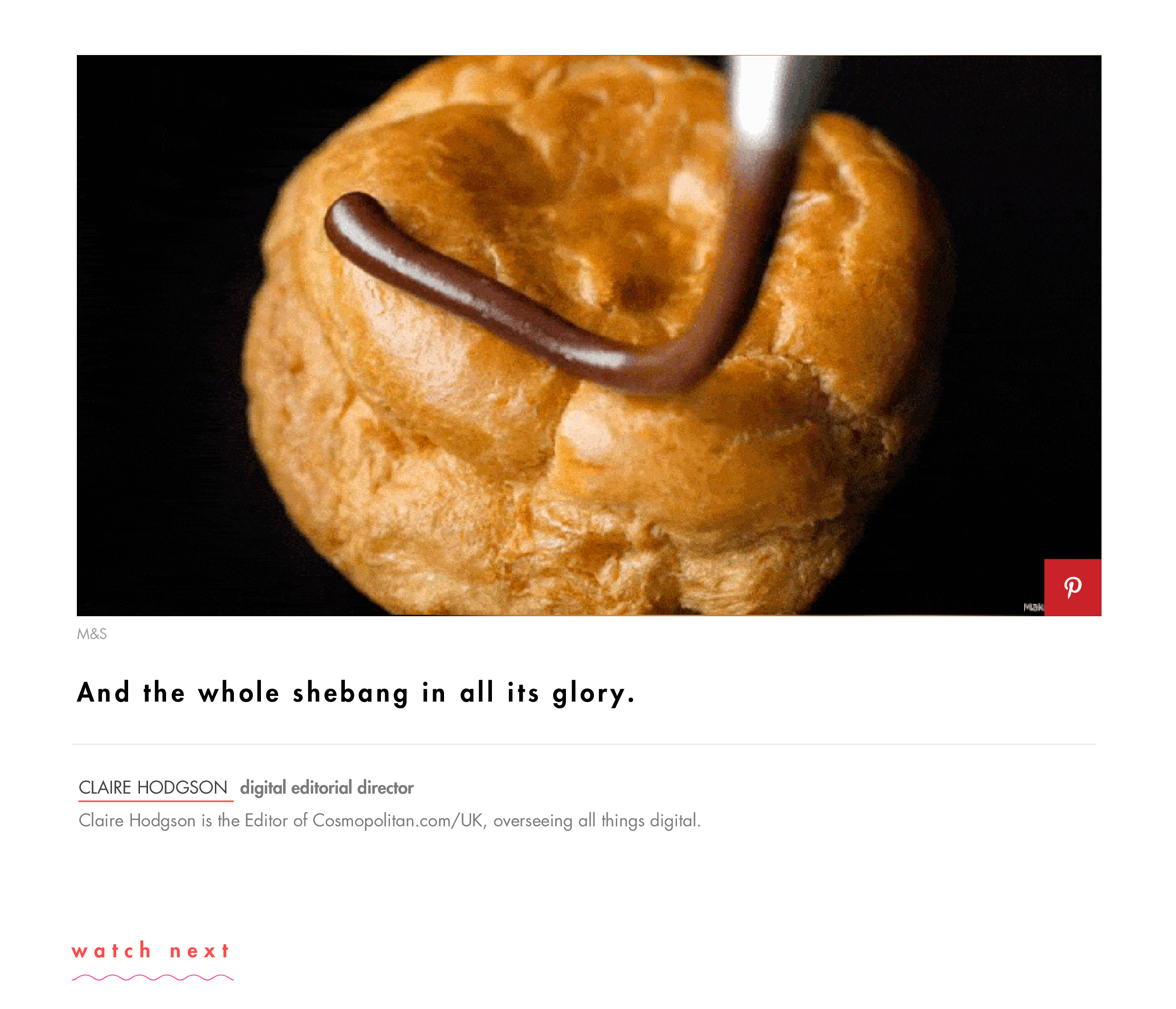

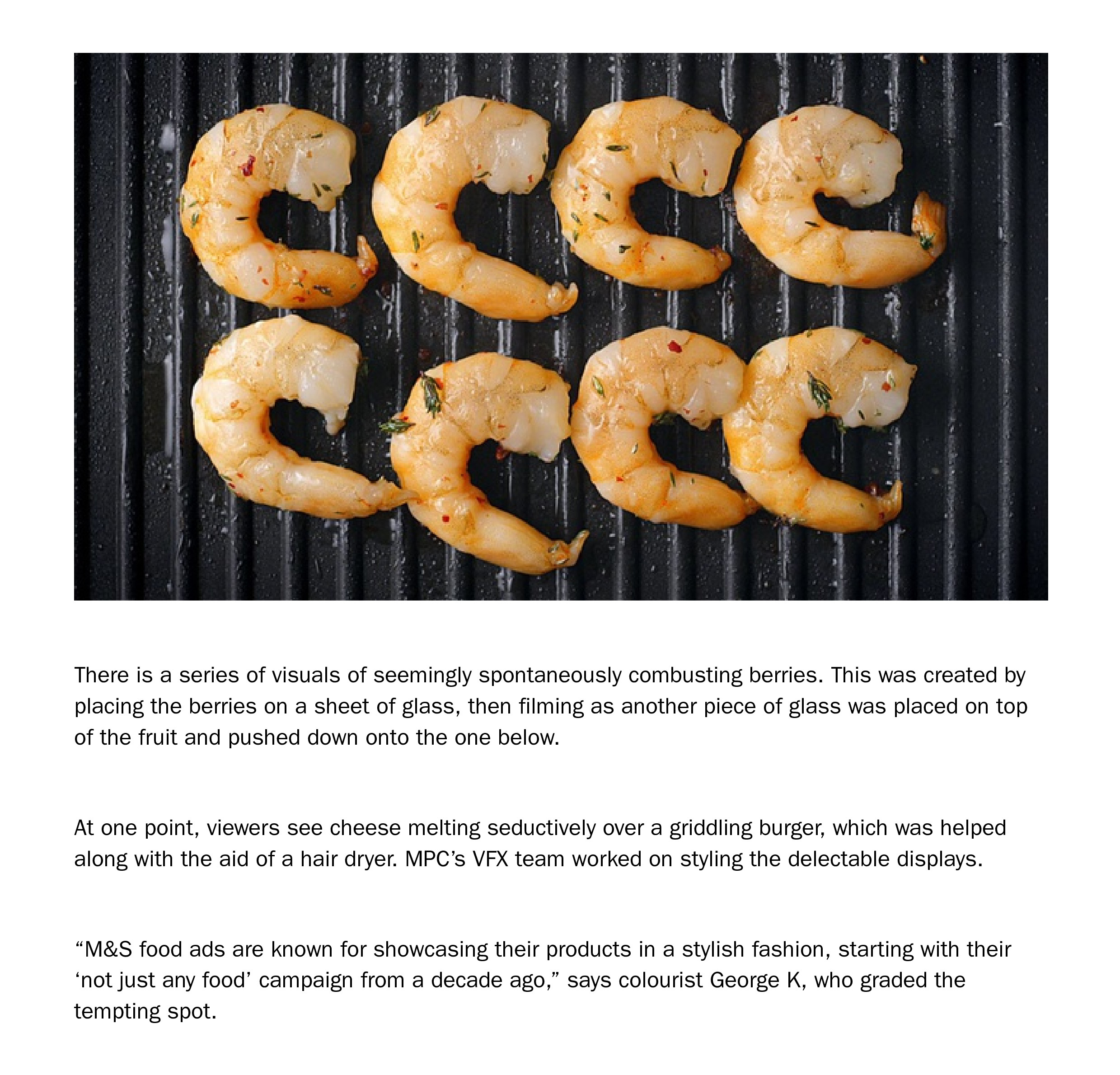

Food was up to quite recently an unexplored territory. This is what makes it fascinating for us. We are artists using food as our playground. Being French also means that we have a cultural respect for it. Colors, shape, complexity of textures, infinite visual associations and concatenation, and in a certain way “porn”.

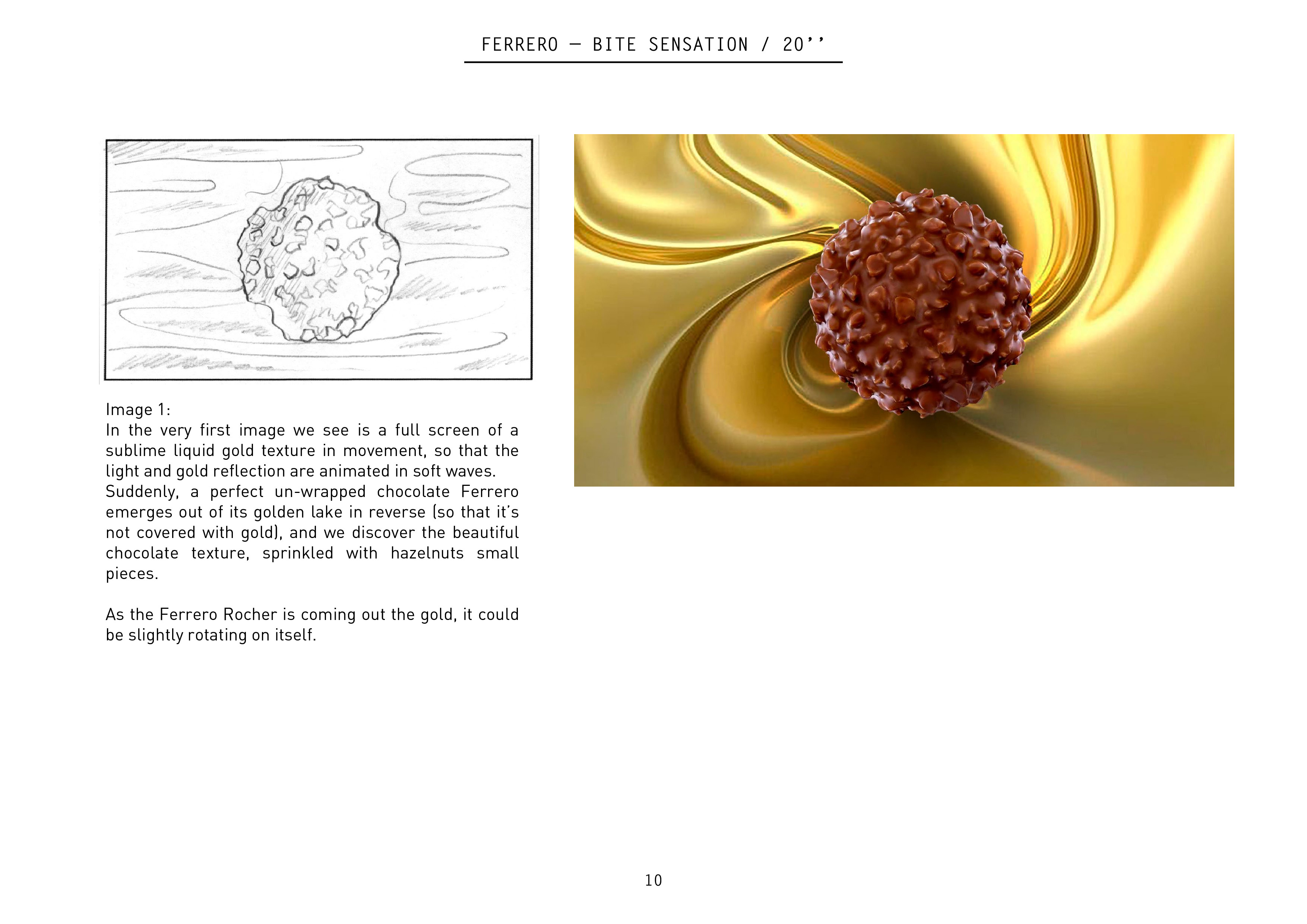

Pornfood meaning that we can induce by the visuals the viewer to “drool” when we film organoleptic textures that provoque desire and satisfaction.

The other challenge was to totally erase human beings. It’s more a philosophical and artistic choice than a necessity for us, and every time we are asked to shoot actors we are happy to do it. But to be able to captivate audience without the acting support is a really an interesting direction. The concept of no-hands-films has led us those last years, but we are in constant evolution, and I am sure it will change.

Being specialized in food give us more freedom than working for other subjects. Everybody has to say something about fashion, cloths, talent acting etc…but very few can have a clear vision about how to stage food, and it gives us a real license for creativity. It’s a niche, and that’s what’s great about it.

4. What kind of experience can you share about food films making? What is the critical thing when making them? Could you explain with 1-2 examples?

One of the critical point is always Time management. When you work with textures you are always surprised by the fact that you cannot really know in advance what shots are going to take more time than others. When you have a long shooting on multiple days your can “deal” with a certain time-elasticity, much better than a single day shoot, when you know that in the same day, whatever happens, you have to “deliver”.

We have to obtain the “visual miracle” in a very short time and sometimes it just does not happens, and you can feel the production team and clients become stressed. We learned how to deal with that quite well. Experience will help of course, but sometimes a simple action like just filling a glass of wine in front of the camera can become a nightmare. Of course one could rely on robotics to do that, but then you might lose all the beautiful accidents that can make the quality of the shot. So it’s all about making the right choices at the right time.

The same critical point goes when writing the scripts. We have to constantly evaluate the “is-this-going-to-be-possible?”. It’s great to have ideas, but they have to be somehow realistic and credible, and sometimes we are not really sure of way the texture will behave. There is a lot of randomness that we don’t control. We often start over and over again to get the right movement or action. We do work with some great SFX teams that we constantly challenge with our crazy ideas, as we took an ideological posture with Philippe not use 3D, and to always film everything for real. Many people think we use 3D, but I can assure that we don’t. We do composite a lot though.

5. Why do you think your work is attractive to the audience and help the brand grow? Can you share one of your favorite works?

I think that what attracts people to our work is that we are often “on the edge of credibility”.

We play a lot with illusion, like a magician who will suddenly speed up a gesture to hide the tricks. The rhythm will help us to create this magic. For example we also very often defy gravity, or normality, in order to give a sense of quirkiness. Make it a bit “weird” to get more appeal or unexpectedness. We also try to show details that people usually don’t really see, emphasizing a certain playfulness with our camera. The slow motion Phantom camera really helps the observation of the unseen.

The other attractive thing is that our scenes are always “in action”. The common question for us is “how are we going to activate this image”. No time to contemplate, the textures are always animated in order to keep the tension of the viewer.

6. How’s film creativity different from the general creativity making?

To accept to work as a team with other people. Even more, to admit the power of a team, like a football player.

It is much easier for Philippe who is an ex Creative Director used to commission other artists. I am a bit of “a control freak” and that makes me makes me suffer more than him, and probably others too. This is where we are really complementary.

Nevertheless our team is much smaller than a conventional cinema team, and we try to keep this “boutique” home-made atmosphere. The idea is to never lose the “primal vision” of the film, and keep an eye on everything. We always work with the same team, and we all know each other really well, and that gives a lot of fluidity to our relations. When there is a difficulty, we naturally team up all together to find solutions. It’s very democratic!

A good team is like a good wine and it’s years of maturation. We where lucky to achieve this.

7. How do you usually allocate work between you two and collaborate with other members in your company? How’s your creativity making process usually?

We both do everything, it’s democracy again. We try to put our ego’s on the side of our relation.

We do fight a lot though to defend our personal vision of the film, but this is what makes our treatments so rich.

We usually take two days to write a script. The first day is only dedicated to brainstorming, and we throw as much as ideas as we can. Phillipe does quick drawings as we

speak to keep it as a memo. The next day he does the drawings, always in black and white. I love the simplicity of his style, and he really has a camera in the eyes. His drawing treatment is very different of what would provide a rough-man or illustrator . I take care of the writing, and I am extremely precise in our explanations. It’s the main secret to win bids. We also try to control as much as we can the art direction of the treatment, and exchange a lot with the creative team doing the lay-outs in the production house. Same goes for the mood boards.

8. Could you tell me an unforgettable thing during you two’s collaboration?

Sometimes the shape of an object, a texture or anything else can slowly become sexually evocative. We remember this time when breaking a poached egg was really reminding a close up of a “very different” scene that could have been extracted from an X-rated movie. Nobody was saying anything, but everybody was thinking the same thing. It was at the same time really evident, and somehow quite understated. At one point the producer “played” his job, and said it, which meant that we had to reshoot the whole scene. It was a good laugh for everybody. It’s foodporn after all !

We have hundred of anecdotes with our job, but that’s another interview.

9. How will Foodfilm or you personally partner with Stink? What do you think you will bring to Stink’s team through this partnership?

We are very excited with this new partnership, and as we are quite easygoing, it should work really well.

Being represented by Stink is a caution of creativity, so we might have to fight less to defend bold ideas. I don’t really know if Stink represents a lot of other table top directors in their international “spiderweb”? I think that the food film market is really huge, and still growing. So if we can fill this gap for them it’s really a great win-win association. Let’s talk again about it in a year time!

Interview for Quad

* Comment travaillez-vous en tant que duo ?

MR - En fait malgré que nos visions soient proche, on est rarement d’accord sur sa mise en œuvre.

Ça crée des discussions, de l’auto censure, parfois des tensions. Mais on a l’intelligence de ranger nos ego au placard et on finit toujours par se mettre d’accord. L’avantage pour nos clients, c’est que puisque beaucoup de choses ont étés discutées entre nous avant de présenter nos scripts, le bénéfice d’enrichissement est réel.

Le secret entre nous c’est que chacun apprécie l’autre énormément pour ses qualités artistiques, et donc ça marche. On a pas chacun « sa plate-bande » comme parfois d’autre association d artistes. Malgré nos formations différentes, les portes sont ouvertes sur tous les sujets, et notre relation se cristallise dans une bienveillance Socratique. Il y a beaucoup d’attentes de la part de nos clients, et à deux, on les gère mieux!

PL - Michael et moi nous connaissons depuis un certain nombre d’années. Je dirais que sans avoir forcément la même façon de fonctionner, nous partageons en tout cas toujours les mêmes critères esthétiques.

Quand un projet arrive, nous cherchons d’abord à voir s’il peut nous permettre de réaliser des images intéressantes. Il faut autant que possible garder une vraie motivation sans laquelle la routine s’installe vite.

Puis nous nous asseyons tous les deux autour d’une table pour « écrire » le film.

Il y a parfois un premier script d’agence que nous reprenons avec nos intentions, mais il nous arrive assez souvent de devoir créer l’histoire de toute pièce.

Alors, c’est un pingpong des deux ou trois jours. Au final, quand nous sommes d’accord sur le scénario, je dessine toutes les images du board et Michael rédige une note d’intention, ainsi que les légendes des images (très souvent en anglais).

Sur le tournage la complémentarité joue aussi. Mais pour ma part je ne suis absolument pas assez technique pour assumer certains aspects, que Michael maîtrise mieux que quiconque.

* Comment avez-vous plongé dans l'univers de la vidéo de food ?

PL - En tant que directeur de création, et avant de me consacrer pleinement à la réalisation de films avec Michael, j’étais en charge la communication de la marque Picard. J’ai très rapidement voulu travailler avec Michael qui de son côté avait déjà fait le choix de la photo culinaire. Nous avons créé ensemble l’image de cette marque.

Nous avons toujours cherché à faire évoluer la photo dans le domaine de la cuisine. A l’époque la tendance était plutôt à des images très « terroir français »

MR - En ce qui me concerne par le plus grand des hasards.

J’ai commencé à travailler en tant que photographe dans l’univers du luxe, et j’ai eu la chance de pouvoir signer de grosses campagnes de pub assez rapidement.

Plus tard on m’a demandé de faire du food, mais j’étais pas trop tenté.

J’ai finalement adoré l’expérience, et j’ai pu grâce à cela trouver un nouveau champs d investigation visuelle, très riche et avec peu d’aprioris.

Paradoxalement, en France personne ne prenait vraiment le food au sérieux il y a 15 ans. On parlait plutôt de « photo alimentaire », et les DA était rarement à la recherche d’une approche engagée d’un point de vue artistique.

Les Anglo-Saxons (Anglais et surtout Australiens) étaient très en avance sur nous en terme d’imagerie culinaire.

A l’époque on se cantonnait à des approches encore « très terroir » ou bien « maison de campagne ». Tout était à faire!

Il fallait trouver un style, une identité visuelle, et j ai décider de me concentrer la dessus.

J’ai rencontré Philippe alors qu’il travaillait sur le budget Picard, et on a travaillé ensemble pendant plus de 15 ans sur ce budget.

Parallèlement j ai réalisé une trentaine de livres culinaires, ce qui m’a permis de rencontrer beaucoup de grand chefs. J’ai re-découverts à ce moment là le vrai plaisir de « création » photographique publicitaire!

C’est un sujet inépuisable et hyper créatif.

Les chefs sont entre temps devenu des rock stars. Le sujet est devenu « tendance » et notre travail a été très valorisé.

* A chaque tournage vous expérimentez de nouvelles techniques créatives. Hormis l'acquisition d'expérience, où est-ce que vous puisez toute cette inspiration / ces idées pour obtenir les effets voulus ?

MR - La publicité fait réellement appel à des qualités artistiques. Donc à notre manière on arrive à exprimer nos envies. Ce sont justement ces « envies artistiques » qui nous font avancer. Le reste n’est que truculence, retour à l’enfance, au jeu, au pur plaisir visuel. Les films, on les fait avant tout pour nous mêmes.

L’inspiration viens de nos expériences de vie. En ce qui me concerne je me suis occupé pendant plusieurs années d’un collectif de cinéma expérimental.

Je suis aussi un photographe passionné, et il y a toujours eu un jeu de vases communicants entre mes réalisations personnelles et mon travail publicitaire.

En ce qui concerne « les techniques », je suis un vrai geek en informatique, et la création digitale me passionne. C’est le côté artisanal de notre travail qui est passionnant.

Philippe aime travailler avec ses mains. Là encore on se complète. Il y a beaucoup d’astuces réels dans notre travail, qui se prolongent grâce à l’outil numérique.

En revanche on ne touche pas à la 3D. C’est une frontière qu’on ne souhaite pas franchir pour l’instant, car elle nous parait antinomique avec le food, même si ce domaine me passionne.

C’est donc plutôt une « posture », et une manière de souligner que tout est construit « in-camera », et que « on se bat durement avec la matière » etc…

Les inspirations sont donc multiples, mais aujourd’hui tout est inspirant, et en particulier Instagram.

PL – Les effets que nous recherchons sur chaque nouveau projet sont là avant tout pour servir l’image ou le montage. Nous essayons de réaliser des images encore jamais vues. Dire d’où viennent les idées, c’est assez difficile à dire, mais les brainstorming sont parfois houleux…

* Le projet le plus challengeant / ambitieux que vous ayez eu à réaliser ? Pourquoi ?

PL – J’aurais tendance à dire que les projets vraiment ambitieux ne sont pas très fréquents. Mais qu’est-ce qu’un projet ambitieux d’ailleurs ? Nous cherchons le plus souvent à amener même les projets les plus simples vers quelque chose d’ambitieux. A notre niveau du moins.

Les projets les plus créatifs, nous les avons certainement eus à travers les films Marks & Spenser ou sur certains budgets cosmétiques.

MR - Le projet le plus challengeant est toujours le dernier projet en cours.

En fait, chaque projet est un challenge en soi, et on a la chance de pouvoir les choisir.

Ce qui compte avant tout c’est de nous étonner nous même.

Le plus grand compliment en ce qui me concerne, viendra d’un commentaire positif fait par Philippe…

* Le produit (aliment) le plus cool à shooter ? Pourquoi (texture, possibilité de création, etc.) et/ou celui le plus compliqué à shooter ?

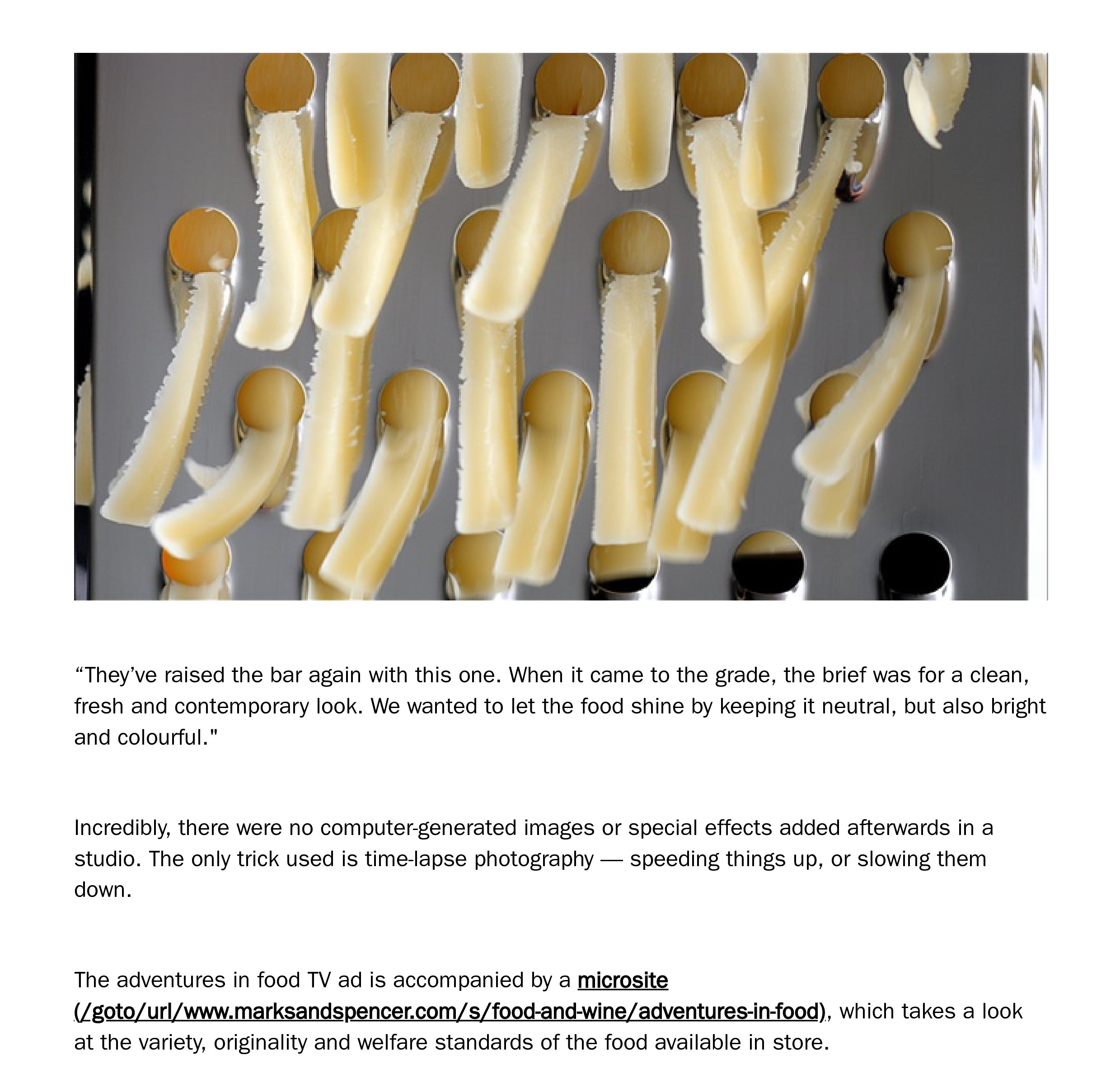

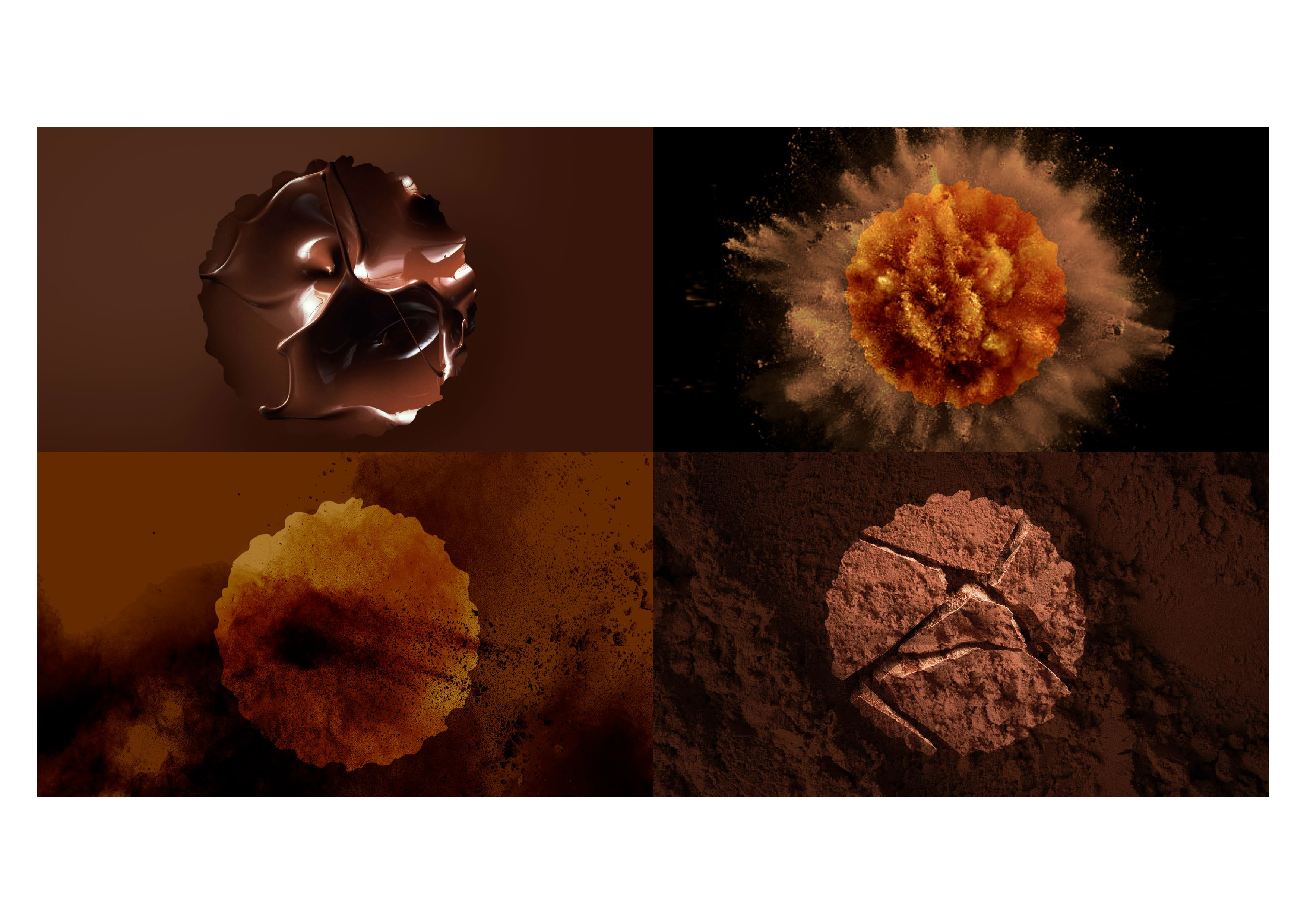

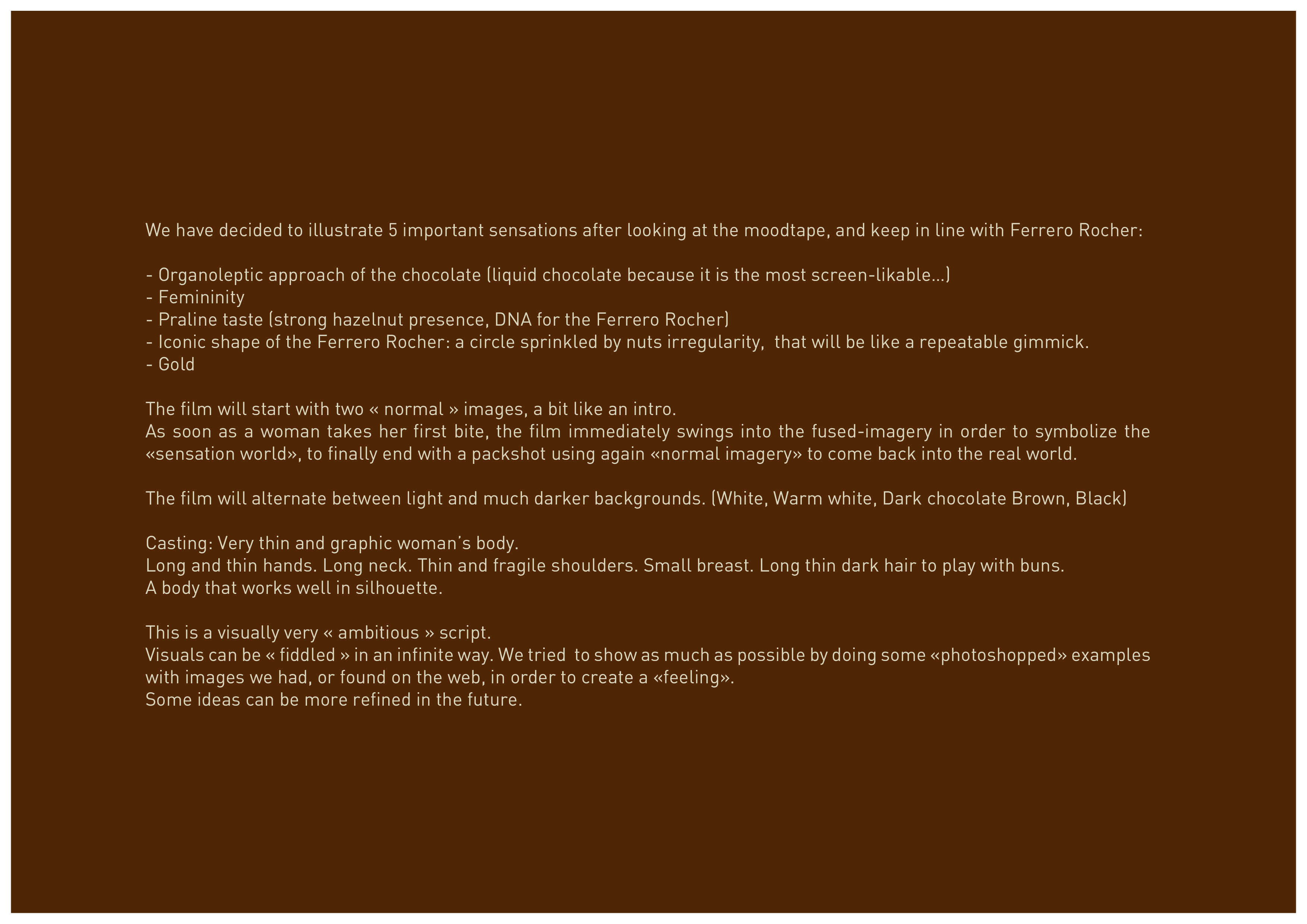

MR - Le chocolat.

C’est une texture très photogénique du fait qu’elle peut exister sous plusieurs formes: liquide, solide, poudreuse, glacée…Mais c’est aussi une texture qui pose des challenges, car elle fond rapidement sous les spots, et donc il faut trouver une méthodologie particulière.

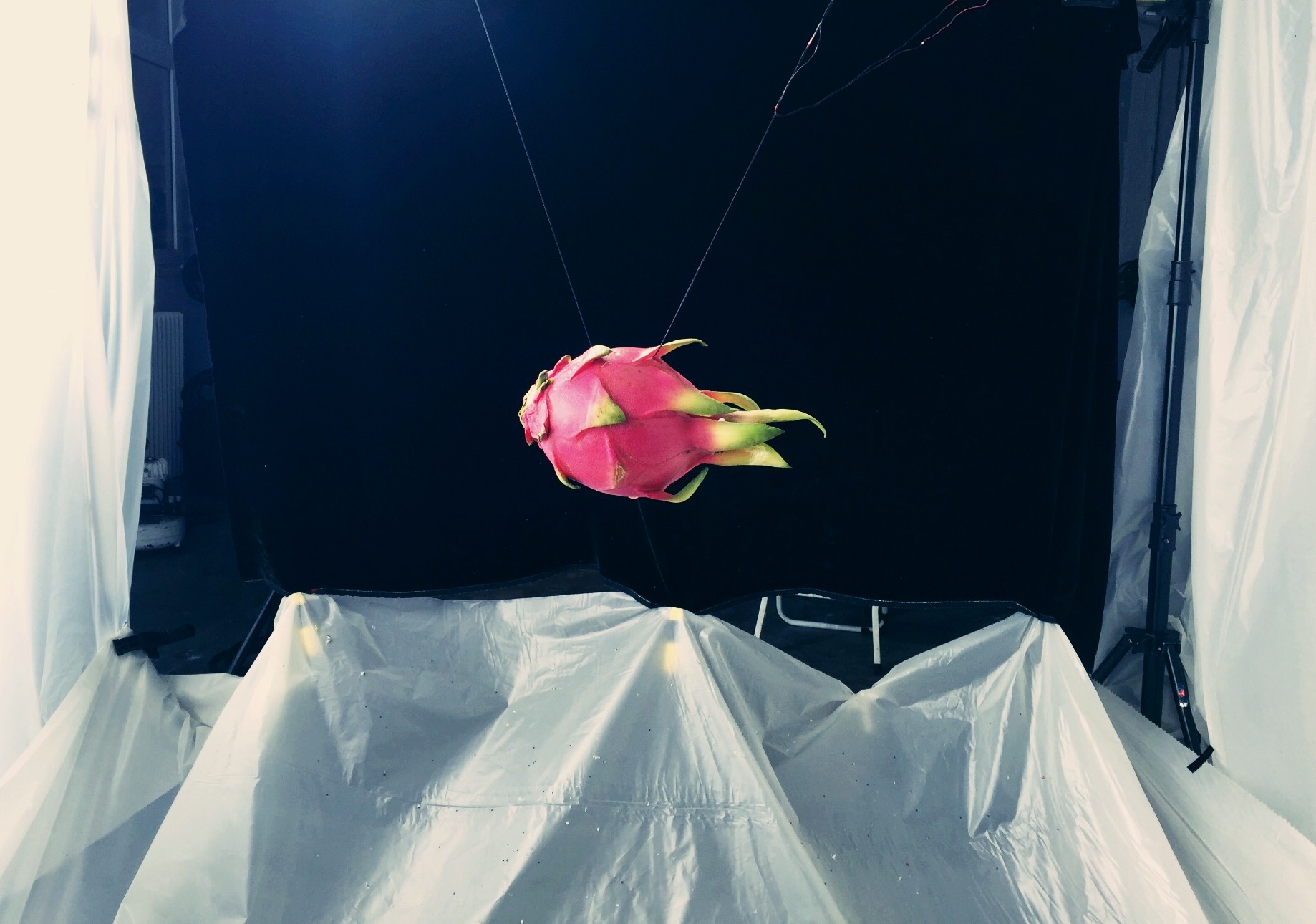

Beaucoup de nos films sont des « no-hands-films » sans aucune présence humaine, et pourtant nous faisons du « Foodporn d’action ». Il y a peu de contemplation dans nos images. Il faut donc trouver des astuces pour « activer » les textures, leurs donner vie. Il y a bien la gravité, le souffle, les chocs, les fils de nylons invisible, les réactions chimiques…mais en fait la grammaire est assez restreinte, et il faut composer avec. C’est justement cette restriction qui nous amène à être créatif.

Le monde de la cosmétique nous à ouvert naturellement ses portes, à la recherche d’une approche plus « vivante ». Avec notre background culinaire, on cochait un peu toutes les cases…de la « crème de beauté gourmande ».

Ce qui est passionnant avec les films cosmétiques, c’est que contrairement au monde culinaire qui s’ancre dans la réalité, il s’agit d’illustrer de manière allégorique les effets (virtuels?) des produits de soins.

Et c’est avec joie et délectation que nous imaginons à quoi peu ressembler l’acide Hyaluronique, les substances hydrophiles, tensio-actives, les nanosphères, les liposomes etc… on adore mettre cela en image!

* Vous avez travaillez avec de nombreuses marques & chefs mais est-ce qu'il y en a un(e) dont l'univers vous fait rêver et pour qui vous aimeriez bosser

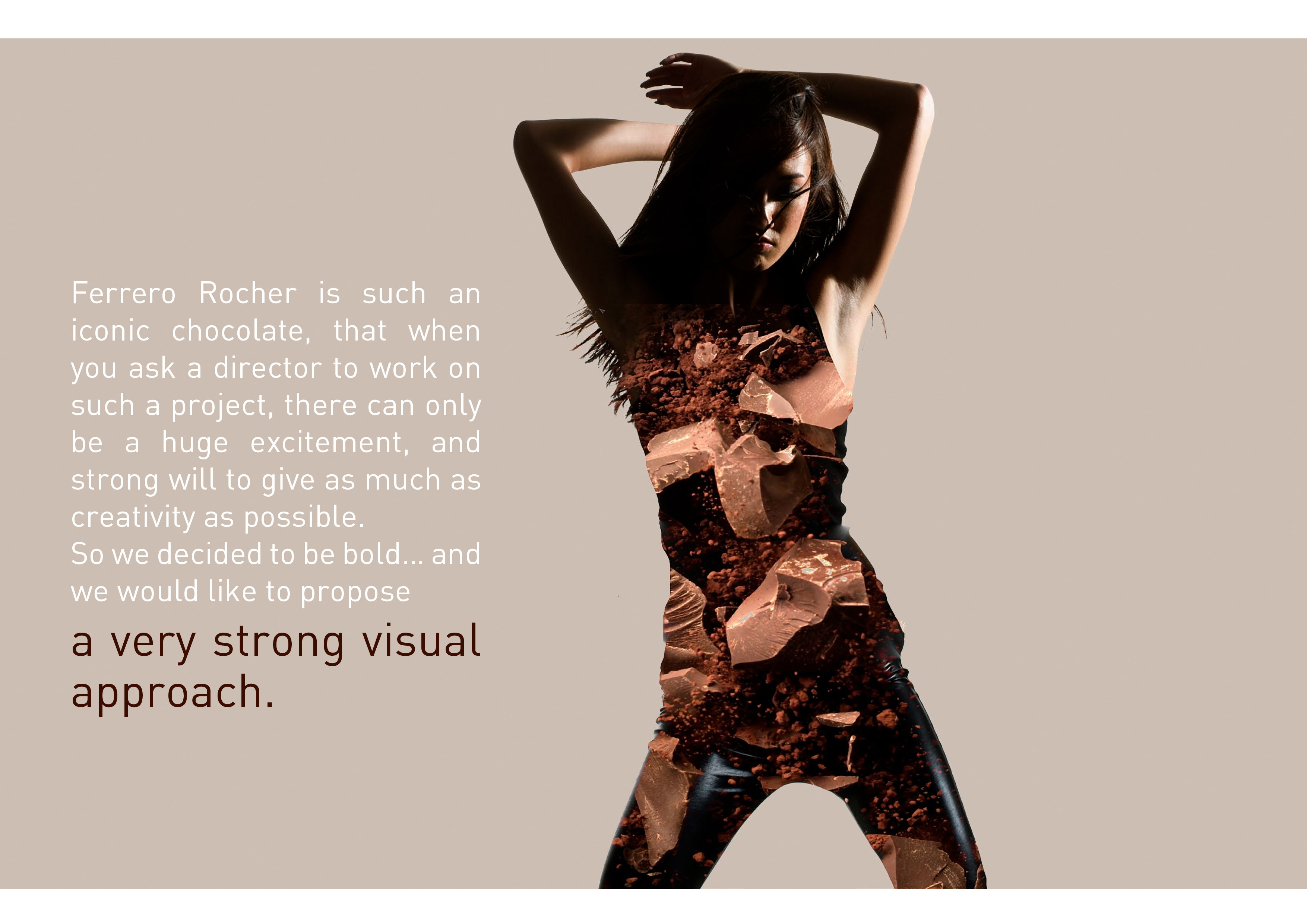

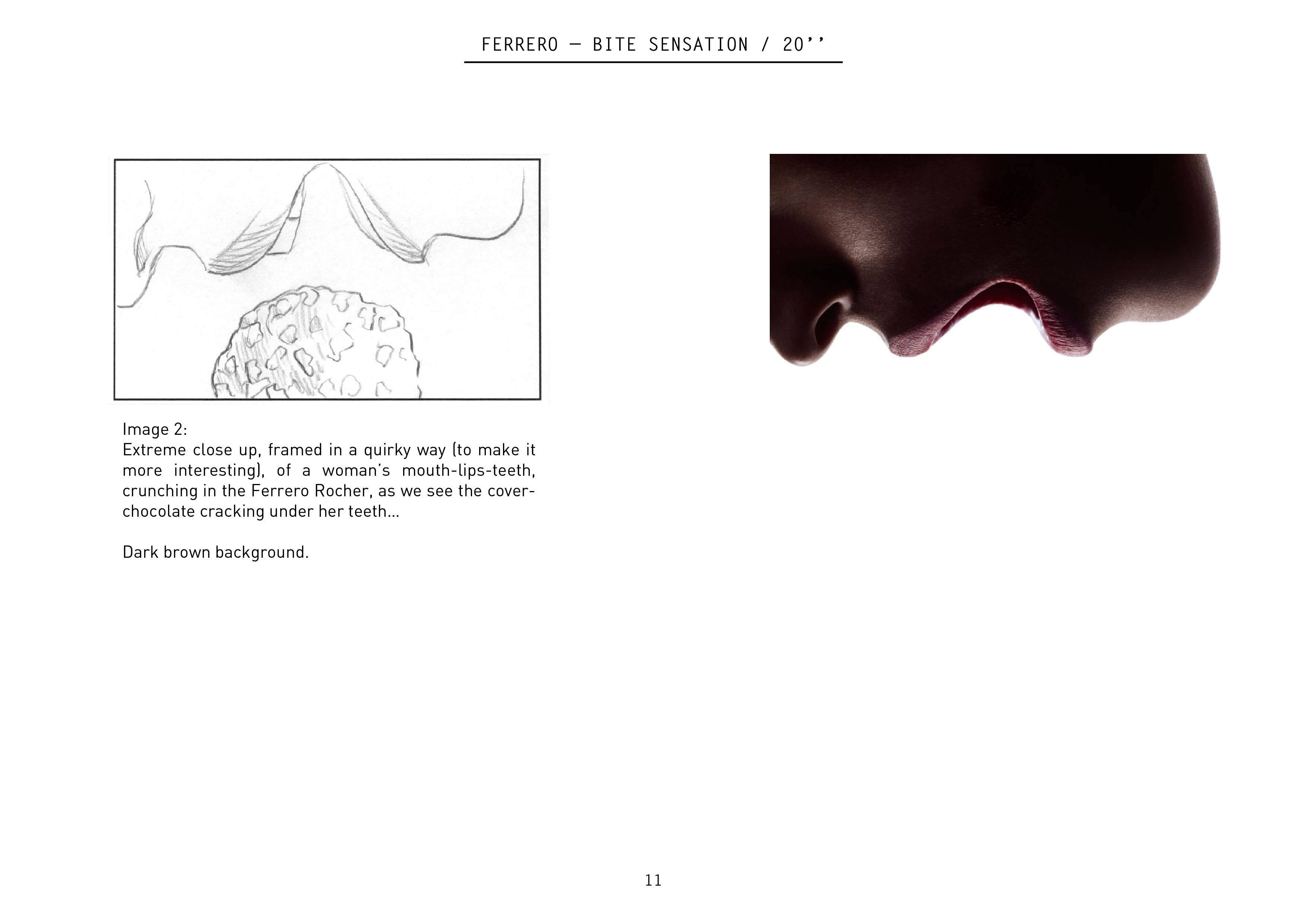

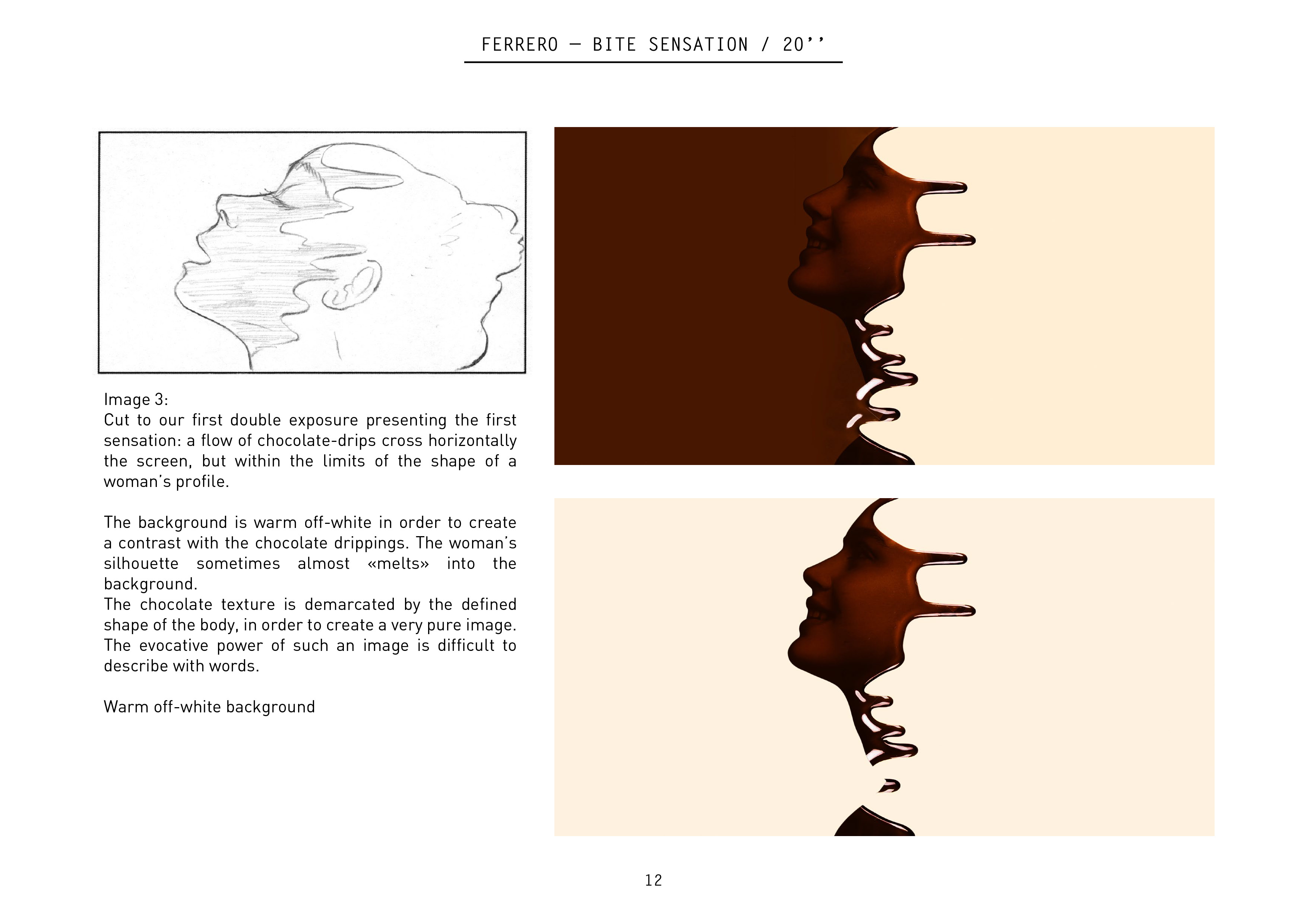

PL – En fait nous n’avons jamais réalisé un film pour un chef, au sens culinaire du terme. Ce serait certainement une expérience très intéressante de mettre en image de la gastronomie haut de gamme. Pour ma part j’aimerais bien étendre un peu notre terrain de jeu et intégrant plus souvent des « éléments humains » à nos images.

Je veux dire par là que je ne souhaite pas réaliser des véritables comédies, mais plutôt utiliser le corps humain, les visages, comme une composante de plus

MR - J’adorerais réaliser un générique de film, un peu comme celui de Dexter à l’époque, mais en encore mieux…

Un film pour un chef étoilé ce serait pas mal non plus, car on pourrait être encore plus abstrait, et réaliser des images assez spéciales, avec des parti-pris encore plus fort.

Malheureusement ils sont plus attirés par l’édition, car elle leur permet d’assoir leur travaux en tant que « Manifeste » pérenne. Mais je suis sûre que cela va changer.

* Qu'est-ce qui vous anime à côté du filmaking food ?

PL – Nous avons tous les deux nos centres d’intérêts. Je suis depuis toujours passionné par l’art en général, mais plus particulièrement par l’art contemporain, qui est certainement une des sources d’inspiration les plus évidentes de la création publicitaire actuelle. Mais la musique, reste la « nourriture » la plus indispensable à mon équilibre. Je m’intéresse aussi beaucoup au cinéma, bien sûr… Bon, mais là, j’ai un peu l’impression de créer un profil pour un site de rencontre…

MR - Continuer mes recherches personnelles, pour assouvir ce besoin quotidien de faire des images, et ne pas trop les les montrer, afin de bien cultiver ce jardin secret et sans concessions.

An Interview of Foodfilm by 'Campaign'

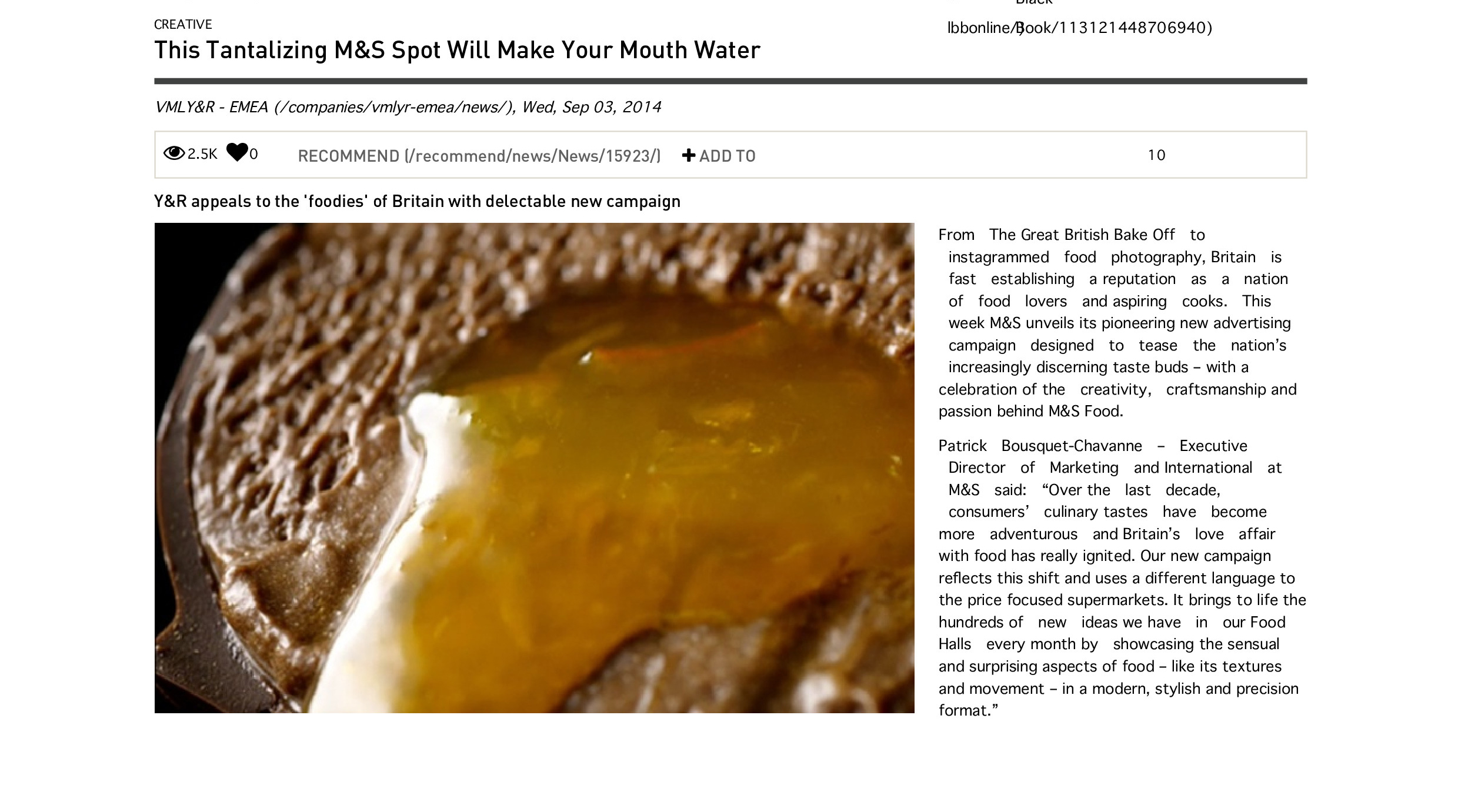

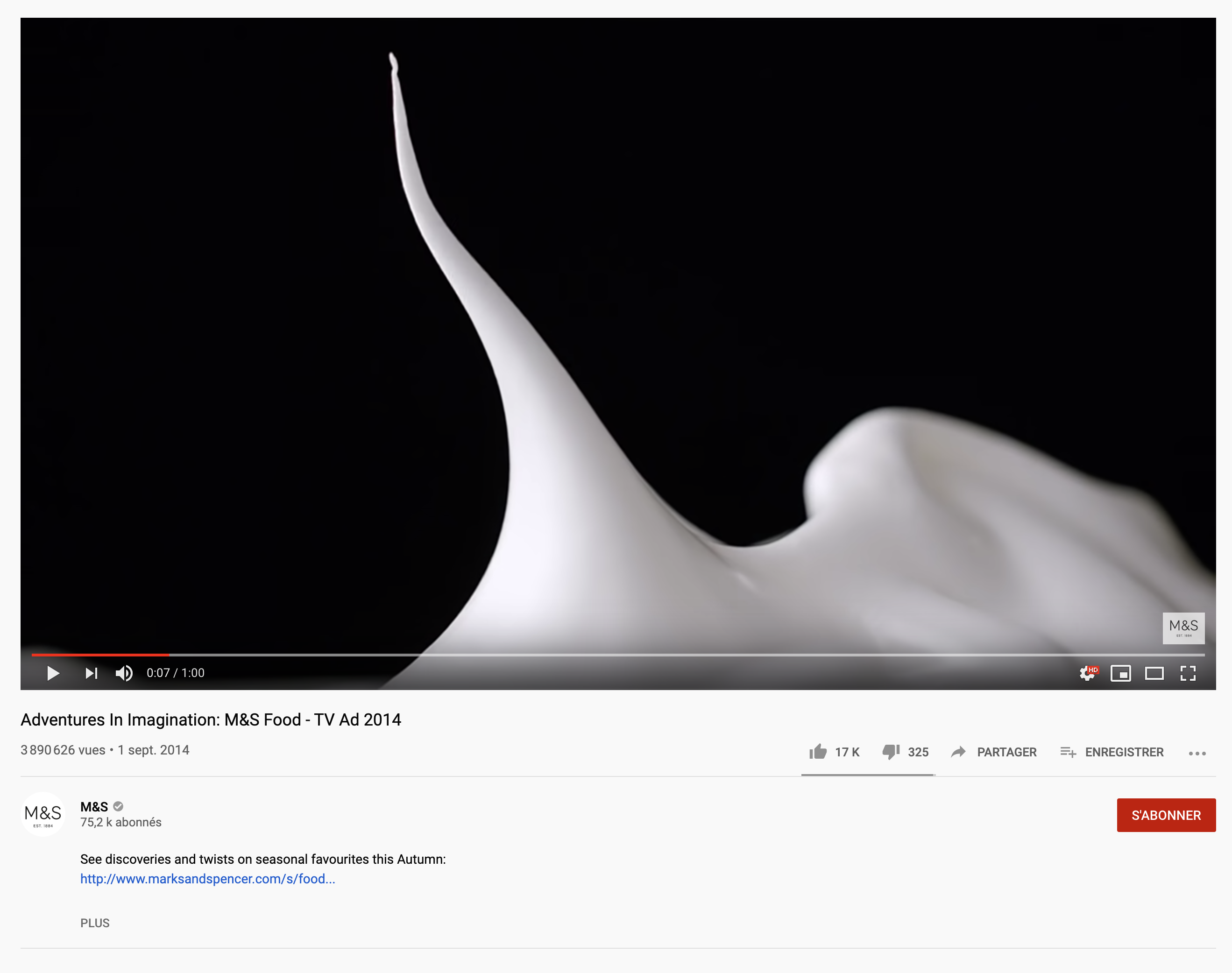

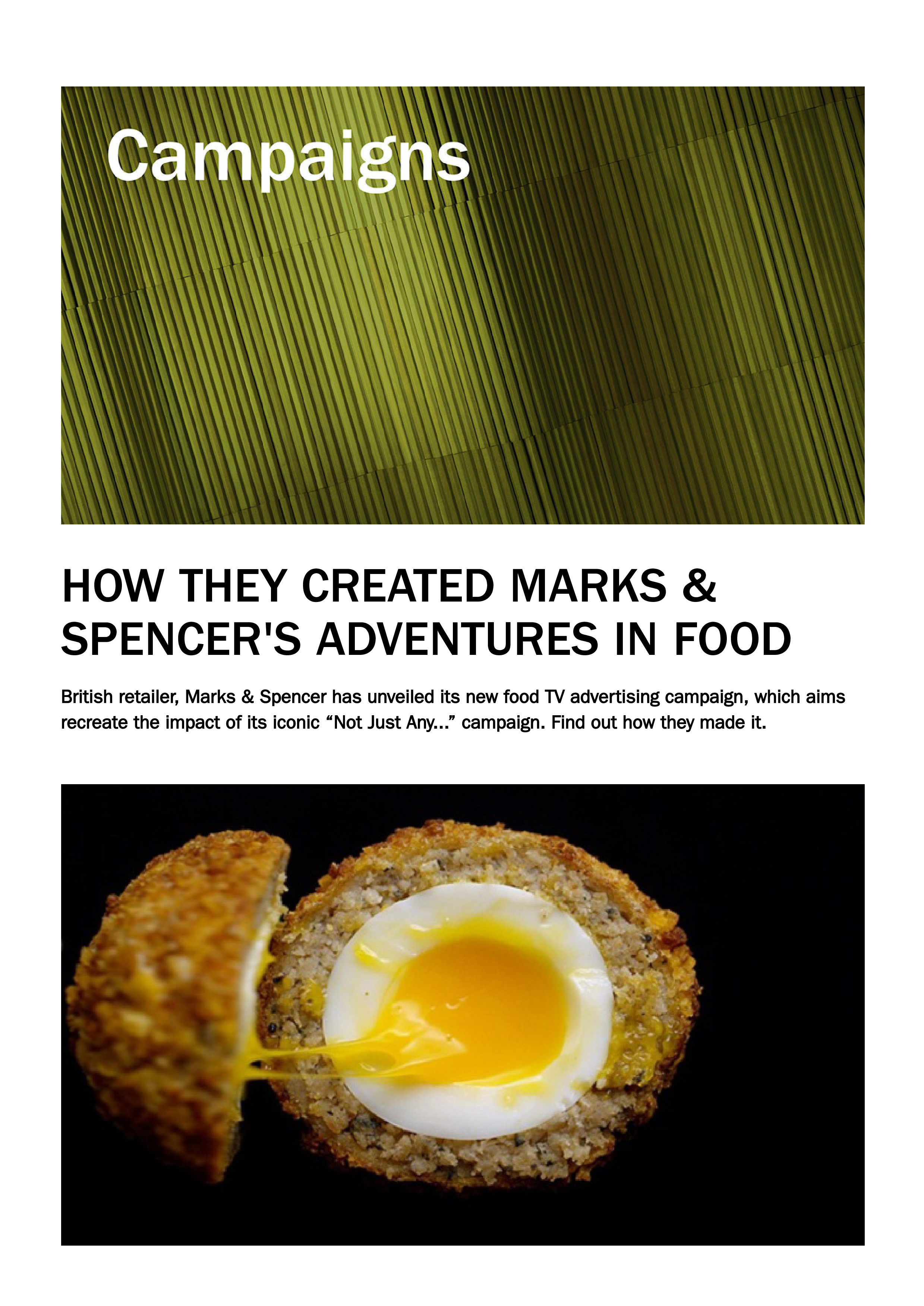

Tell us about the M&S Adventures in Food project? (ie how did they get on board etc)

Five years ago we did a viral web campaign for a French coffee brand and we first tested the concept of a « no-hands-film » : things happening « magically » without human interaction. It was very successful with a few million views on youtube.

When Pip Bishop and Chris Hodgkiss in charge of M&S at YR where asked to « re-new » the food films, they spend a lot of time on the web looking for food directors who would have a different approach to doing tabletop. They discovered our films on our website, made big enlargements of some stills to hang in the office, and waited to see how people reacted to these kind of images.

One day they called us directly in our Studio in Paris and we felt they where really excited and enthusiastic about working with us.

We invited them for lunch in Paris, proposing one of the best foie gras we could get our hands on to greet them, to discover afterwards that they both hated foie gras…Nevertheless the contact was great (we quickly went to buy some salads!), and we all felt very comfortable with the idea of working together, on such an iconic budget like M&S, that would involve a lot of creativity.

The deal was to make a « test film » called Adventures in Imagination, that would be rather generic about the brands creativity, and see « how it goes »… Mark Roalf, head of Y&R, and M&S liked it very much, so they decided to launch it, and I think the public received it really well.

Since then we have done more than 25 films…in one year.

What equipment do you use to film the food?

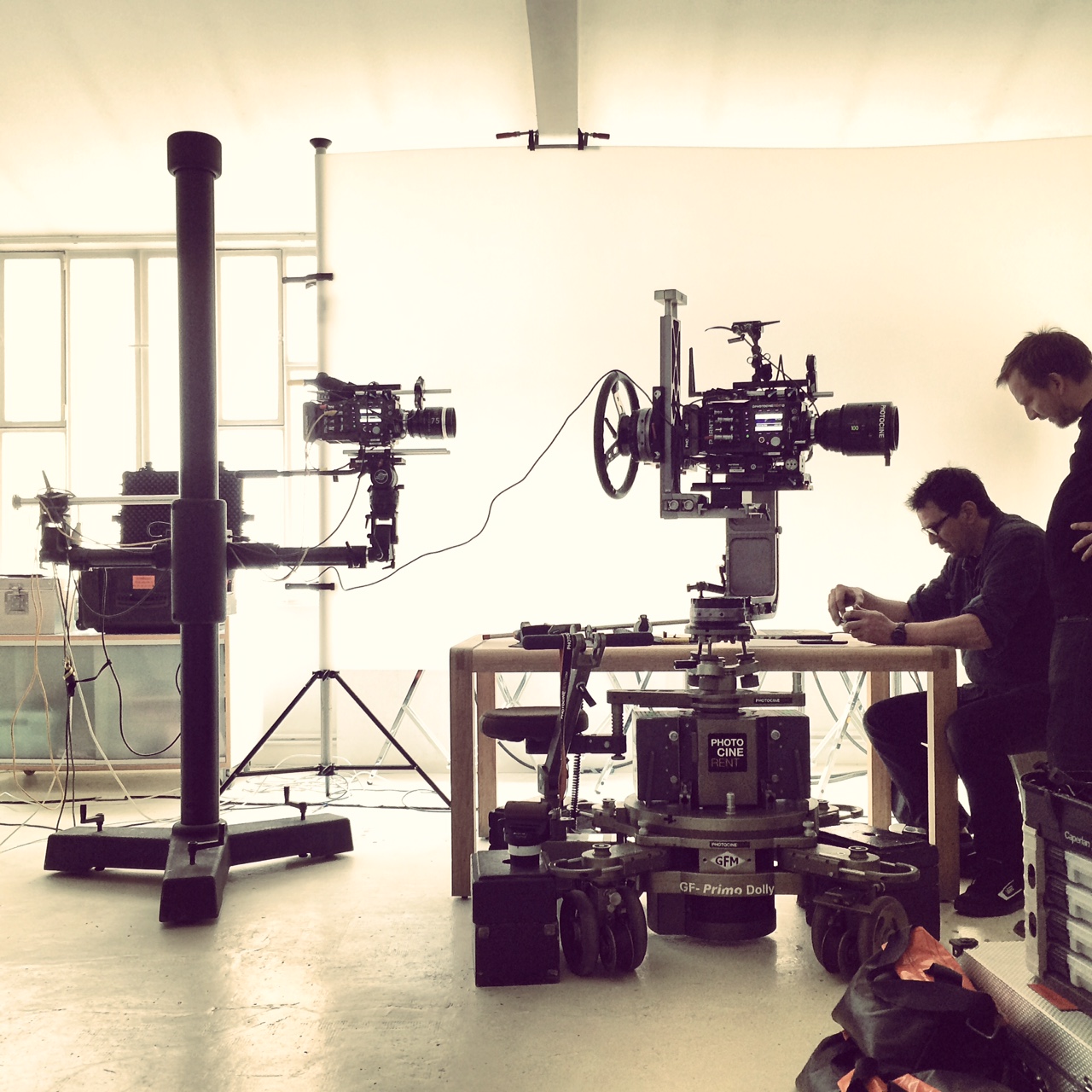

We use a Red Dragon (6K) and the lights are Arri M40.

The Red Dragon has the possibility to shoot at 200 FPS for a mild slow mo, and since the pace of the film was quite rapid, we knew we did not need to use to much Phantom high speed cameras because they are quite heavy.

We prefer the versatility and size of RED cameras since we operate them ourselves, surrounded with a small team to be more creative.

The Arri lights were great because they don’t heat too much, and food stays fresh longer on the set. Still we do use 30k of light on each of our sets.

How do you prepare the food? (ie how many times do you have to practice a shot? Do they paint or treat the food to make it look good?)

In the most « natural way » we can possibly do, without any sort of trickery. It’s a false idea to think that nowadays food is mistreated or « painted ». It just does not work, especially when it’s shot in very high definition

We do not use either CG or 3D. All our effects are inspired by Melies, a film maker from the beginning of the century, based on editing. There is something quite « vintage » in our approach on how-are-we-going-to-do-this-shot?

Since we don’t « cheat », we do practice many times the same shot before being succcessful with it, persisting until we get the « perfect » movement or action. Sometimes its 20 times!

What are the biggest challenges when filming food?

1 -To keep track of time.

Everything is enormously time consuming when you just work with textures. The elegance is to make things look very simple, even when it’s not.

Just to fill a glass of wine from a bottle from high above can become a desperate task.

We spend more time cleaning the spills…than actually filming them.

2 -To be confident that the ideas we propose when we write the scripts, will actually work on the set! We don’t always have time to test everything.

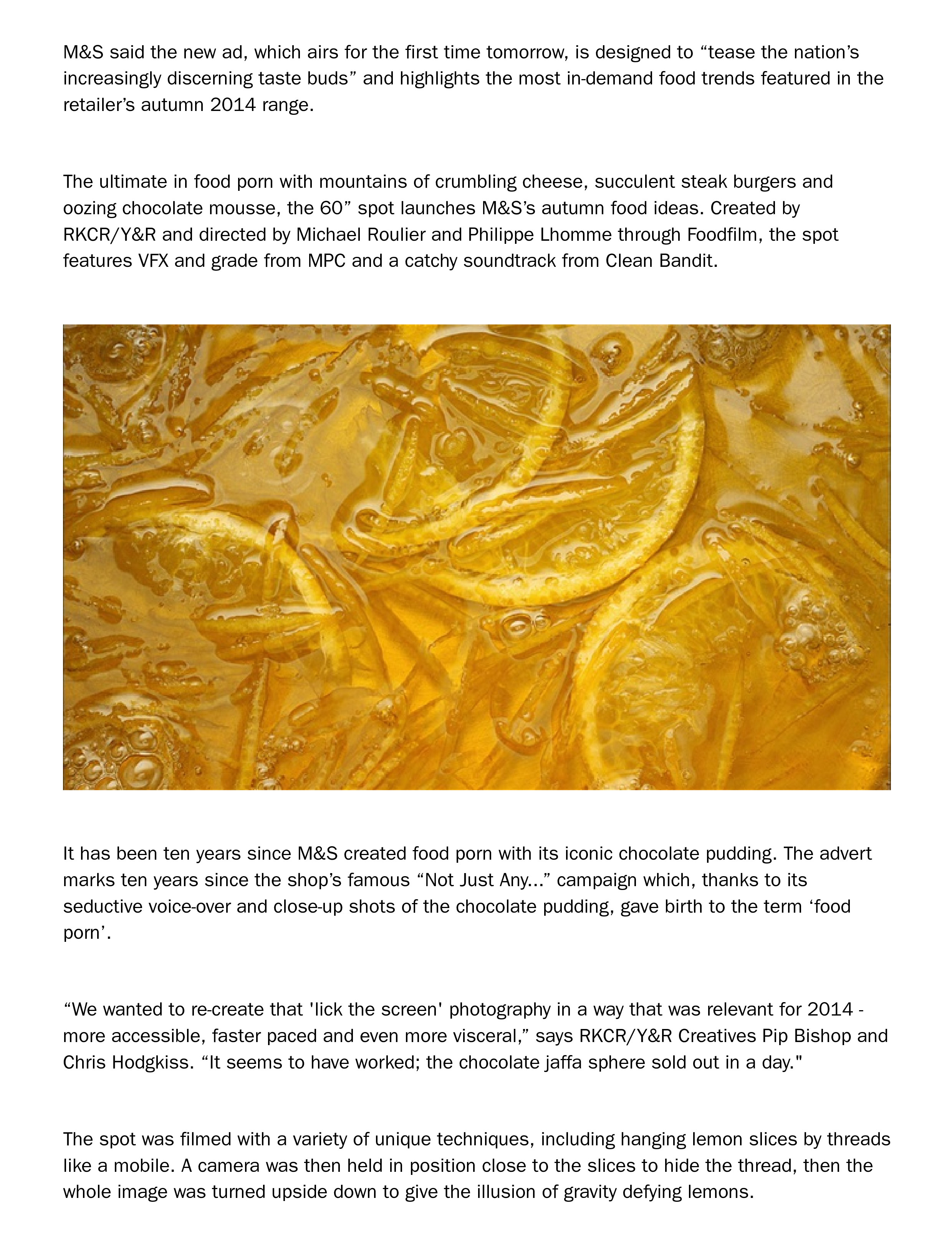

Can you tell us some of the more surprising tricks you use? (ie Hairdryer on cheese, strings on lemons etc)

Since our « rule » is to never see hands, we have very few parameters at our disposition to make thing moves : gravity, wind blowing, invisible strings, heating, stop motion, timelapse and above all smart editing,

This limitation makes us become more creative.

One of our « signature tricks » is to bang with our hand under the table, so objects start jumping in the air. We refined this idea to the extreme, using it in a lot of different ways.

How did you get into food film directing?

Philippe and I come from a print background.

I have been a still life photographer working in luxury and cosmetics.

More than 10 years ago, Philippe who was creative director at DDB Paris proposed me to work on the French « iconic » food client Picard.

We shared the same thoughts that it was actually more creative than most other subjects in the advertisement world.

Years after that we decided to start directing food TV spots, taking in account all our previous food experiences. It was about time to re-new the subject.

Is it just food you work with or other substances as well?

The frontier between food and other subjects is very thin.

We work with textures, so quite a few cosmetic brands consulted us to work for them.

The latest spot we did was quite experimental for Yves Rocher.

But we feel we could work on any subject.

What other ads have you worked on?

Please refer to our website

www.foodfilm.com

What inspires you?

I think that we get quite inspired by each other. One starts, the other ends.

We are a good ego-free combination because we have different backgrounds.

One day Philippe arrived at the studio saying we should not try to shoot « cinema » anymore, but « moving stills ». That inspired me a lot for instance.

What inspires us overall is contemporary art and experimental films.

We are also inspired by all the ideas we have not had yet!

IN CONVERSATION WITH FOODFILM

ROBERT PAYTON * AUGUST 23, 2022

How it had all begun? What’s next, and where the glory of food is. Rob Payton – passionate film director, in conversation with Michael Roulier and Philippe Lhomme, better known as Foodfilm, the iconic duo.

R: How did you start out, what was your background prior to coming into…I don’t want to use the word ‘tabletop’, because it’s too narrowing, but food work. Was there a family background? Was there a passion for food?

Michael: No, no. No previous passion for the food at all. Or rather no views in that regard. In the beginning I wanted to be a reporter. I was always passionate about photography since I was very young … oh and I studied philosophy.

Food Photography came much later. Basically, I was doing fashion, like a lot of young photographers do, then I started to do mostly still life. I found food completely by chance, at a moment, when food was starting to become something interesting – It was in the 90s – 1995 I would say. Some beautiful books were coming out, photography was becoming interesting. Then, one day, there was a call from Philippe who asked ‘would you like to try’? and I said ‘yes, why not’… and I just loved it.

Philippe: I was an art director for a long time; before I met with Michael, a long time ago. We slowly moved to the movies, because we were interested in this kind of evolution of our job. I must say that as an art director, I decided to work with the best food photographer in Paris (Philippe and Michael laugh) – that’s why I met Michael.

M: Art directors don’t really have an idea what to do (with food)… I’m not speaking about Philippe – he was a special art director for food. But most of them had no clue about it. So they were relying a lot on the photographer to propose the shots. There was a lot of freedom. Basically I was being paid to be free, which was very cool. I loved it because there were many interesting things to do – very creative.

R: It’s an obvious question when you work as a directing duo – how do you divide your roles?

P: Well, I must say we are quite complimentary. We talk a lot when we start to create a film. I draw all the storyboards and Michael works more on the words. Yet, I think we have the same approach when directing and thinking about things. We both like elegance and playfulness.

M: We knew each other before.

P: Yes, we were in charge of the visual communication of a major food brand in Paris – Picard.

M: So we knew how we could work together before we started making films. We knew what to expect from the interaction. It is really cool with Philippe. The communication between us is good.

P: Of course, we had a lot of freedom at the time. It was more free then, that we can expect now in regards to certain subjects.

R: Do you find now that agencies are being more prescriptive; that they’re less likely to take risks? What’s your take?

P: I think it’s the legals. The lawyers are everywhere. Sometimes we try to implement new ideas with commercials and the lawyers are telling to cut things out.

M: I don’t know if I would say that there is less freedom today. I would say it depends completely on the agency. Some agencies expect a lot from us – almost everything. With others it’s more prescriptive. Then our job as a traditional director is to make the script more round, giving it a reality and a rhythm.

I think today there is less money and this makes things a bit more difficult. Especially the way we like to work. We like to write very rich boards with a lot of images, and of course we have the production calling us to tell us ‘you have too many images, you have to take out a few‘. And we say ‘listen, it’s important that we show this richness’. We were doing what we call ‘no hands’ films a lot.

We understood very quickly that if we didn’t want the viewer to get bored when they see our films, there needs to be action throughout. It’s not just about watching beauty. It’s action, action, action; activating things, finding ideas on how to animate things – so the films have a sort of inner life on screen.

With the smaller budgets, we are limited. We can only do a certain amount of shots per day. For us, that’s a big problem. The agencies are ready to sacrifice a lot of quality for the budget.

Of course, today, when there’s a global budget for 20’ we say ‘ok, we need two days minimum‘, and they say ‘we have two directors who do two 20′ in a day!‘. And we say ‘listen, it’s impossible for us, we have too many things we want to show‘. In the end they start to understand, because our films work – we know they work for the audience. It’s always a fight on our side, because we want a lot of imagery and we need a lot of time to do the shots. We fight for that on all our films.

Especially now, that there are Instagrammers. There are those who will do films that are very cheap, but we have completely different techniques.

R: When I look at your body of work, it clearly has your stamp on it. Can you give me some of the techniques you deploy to create that visual humour and that playfulness?

P: To start with, maybe it’s because we were the first ones to look closely at the food. To look at the details of foods: the textures, the colours, the shapes and all of those things.

M: I think we were the first to do ‘no-hands’ films. This is for sure.

P: That too.

M: Our secret, before technique, is that we invest ourselves in all aspects of the film – not only the writing and the filming. Also the post-production and all those moments after the filming; where there’s actually a lot of space for the magic to happen.

I think in the regular work flow, directors just do their films and then they leave it to other people. We don’t do that. It’s quite difficult to explain to people the way we work. Simply put, we work on our material a lot in post. When we accumulate a lot of material, we can do a lot. Then we control what we do with the material.

It comes down to the tricks; it’s more about the aesthetics that Philippe and I have. It is also about being very graphic with our images. We take a print approach to the images – they’re like photographic tableau.

I remember a small anecdote. When we started doing films, we were working for a coffee brand and there was not a lot of money; which also meant more freedom. Philippe said: “listen, we’re not going to make films, we’re going to make tableau (you know, just animated images)”. From there, we’ve developed a whole grammar scheme; which we have tried to refine over the years. It’s getting harder and harder though, because you really notice more beautiful stuff all around.

For instance, we have a robot – there’s a lot of robotic imagery in tabletop. It was a painful development actually; because people don’t give away their secrets. When you buy a robot, you have to write an algorithm, you need to find someone to write how to make the robot work. So we did all that, but in the end; we’re not really using our robot. There are 2 reasons for that – robotic image means time, secondly people who use robots have no ideas!

If you want to show your ideas with a certain turbulence, with a certain joy; a robot shot takes at least 3 seconds out of your commercial. Then there are images that are very short, but really powerful. We want shots really short and we want them to accumulate those impactful images. I think it’s a good frustration for the viewer, because it makes them want to re-watch the film. Every time they watch it, they find something new. That’s also the richness of our scenarios.

R: One thing (we can talk as fellow food film makers) that constantly frustrates, is this inability to use the two key senses that we associate with food. How do you get that visceral pleasure across when people can’t taste or smell the product?

M: We know from experience, from doing so many visuals of food, where the glory of the food is, where the emotions are.

No matter the subject, we know what to show to make people drool. So we try to mix it all together with beauty and art. Food is something really difficult, because it needs a very specific methodology.

R: Is there a brand or a product that you wouldn’t want to shoot, or do you see everything as a challenge?

M: What we don’t do, actually, and what we’re very lucky not to do, is, demos especially – the 4’ at the end of the film. People come to us wanting a whole film. Doing demos is not my favourite way of working.

Basically, we do a lot of things ourselves. We have the technique because there’s a lot of technicality to our work. I’m quite a geek. Philippe also has a lot of ideas about creating little systems – much more than me actually. When we look for how to create something, he usually finds a simple way.

When we have to work with SFX guys, they’re really expensive – I mean, super expensive. So the problem is that when we integrate them into a shoot, we know it’s going to eat part of the budget and that maybe we’ll have less time for the film. So we try to limit the use of SFX guys, as much as possible and have a lot of in-house little tricks.

We also have our own studio, which, you know, not all the directors have. We have all the tools, so we can create our own rigs.

R: Despite the name, you work a lot with beauty products and wellness products. Do you treat a beauty shoot fundamentally the same way you treat a food shoot, or are you trying to evoke different emotions?

P: Most of the time, I think, for the cosmetics, we have to create things that don’t exist. So, it’s more abstract in a way. The SFX guys are really necessary in this case. At the same time, it’s always the same environment: bubbles and things dripping. Thus, we have to find new ideas. Abstraction is not that easy. Sometimes it’s complicated to create something new.

R: How often do you involve model makers for food?

M: As little as possible, but we have a really good model maker in France. She’s really, really good. Still, I would say as little as possible. Model making, for me, anyway, is not very rewarding. Now, when you do chocolate, it’s good, but when we used other models; personally – I was always disappointed. Food is something organic and it can’t go through resin or things like that.

R: We’ve all been spectacularly affected by Covid, I just wonder, how has the pandemic affected your work? How many of the changes that were implemented because of Covid will you be carrying forward? Were there positive lessons learned from it?

M: Well, there’s one positive thing, one very positive thing. The PPMs are happening on Zoom. We’ve gained some time. The negative part is that the shooting is more complicated. However, it works – we did a lot of them – but it’s more complicated. We lose a lot of time explaining the shots, people are not there, so the approvals are more tedious. The whole process is heavier- but, you know, it works.

P: It works quite well.

R: Your style of filmmaking would seem like a natural one to shoot remote production.

M: I like clients, I like being with them; making them feel out the vibes of the studio. It’s super important for me. Now that Covid is going away, we try to bring back clients into our studio. It’s about the contact, the warmth, and we lost that warmth. It’s much colder over the internet.

I think that we do better stuff when we feel pushed by the energy of the clients.

When a client is happy, it really pushes you (pushes me anyway) as a director, to really please them even more and to be more creative. It gives us wings… you know.

R: You work as a small team, that is something of a ‘cottage industry’ about your work and I don’t mean that in a negative way. I sense your preference is to provide a ‘script to screen’ including conceptualization ?

M: Are you saying that we like controlling everything? That we’re a little bit of control-freaks?

via www.foodfilm.fr

R: I don’t think that it’s about being a control freak. I think it’s about authorship.

M: Yeah, I think it’s very personal. As far as I am concerned when a post-production is not done by us, I am disappointed. Maybe, that is because the people in post-production are less interested in food. They’d prefer to do big fashion films or whatever. To me, the role of post-production is to bring the images to a certain level, to make them more beautiful, more powerful.

But, yeah, I think that part of our success is that we try to control the whole process… maybe we’re wrong to do this?

M: What I know, is that sometimes when we go to work in foreign countries; what we’ve been told by production houses, is that… we have a very strange way of working – we try to do the post-production during shooting as much as we can. It involves long days of work. We film and then we stay late to look at what we’ve done, to start ‘de-rushing’; trying to introduce the effects if there are any involved and so on. That way, we can show it pretty quickly to the clients.

For me, after the first day of shooting, whether you are in for a week or four days of shooting; I like to immediately show what we did that day to the client – already coloured. Even if it’s not perfectly post-produced – we want to make them feel like ‘ok… I’m really comfortable with these guys’. That gives us a lot of freedom later. If people are cool with you, you can really push them into your ideas. So, this is a way of working that is very specific, I think, to us.

Clients love that. Agencies too. So we work that way.

R: What would you love to be shooting tomorrow? If the phone were to ring after we finish this call, what’s the perfect product or the perfect job for you next?

M: Ah, that’s a question!

R: It’s giving Philippe time to think before I ask him. (Philippe laughs)

M: Tomorrow? … I would love to do a small personal project with Philippe, you know? Sort of creative research. We started a series that we called ‘ugly’, with just one film, with an octopus. I like that film very much. So for me, tomorrow I would like to do something like that. That would be my best, next project.

P: Maybe the next one we are going to be briefed for. We have been interrogated for a film only on body and on skin. So it’s a ground that we’ve never been exploring before.

M: It’s actually quite scary Philippe… no?

P: It’s a bit scary, but it’s a new adventure and I think it’s one of the things that I would like to explore. Body as a landscape – could be very interesting.

R: Do you think it is possible to be a food filmmaker and not cook?

M: Yes, I think it could be. Doing food films does not make me hungry. I have a completely different relation with food when it’s an art object, than if I’m eating it. It’s very strange. There’s a complete dissociation. I don’t try to make people drool (with my films). If they drool, good for them, but it’s not my first purpose. My first purpose is to bring out the ‘inner beauty’. I probably have too much of an aesthetic approach.

All the same, it doesn’t make me hungry – making food films. I’m sorry if that disappoints you (Michael laughs).

R: No, I think your clients are very happy. They don’t want to make you hungry, they want to make the audience hungry.

M: Yeah, exactly.

R: That’s perfect. I really enjoyed our chat, thanks guys, it’s been fun.

ROBERT PAYTON

AUGUST 23, 2022

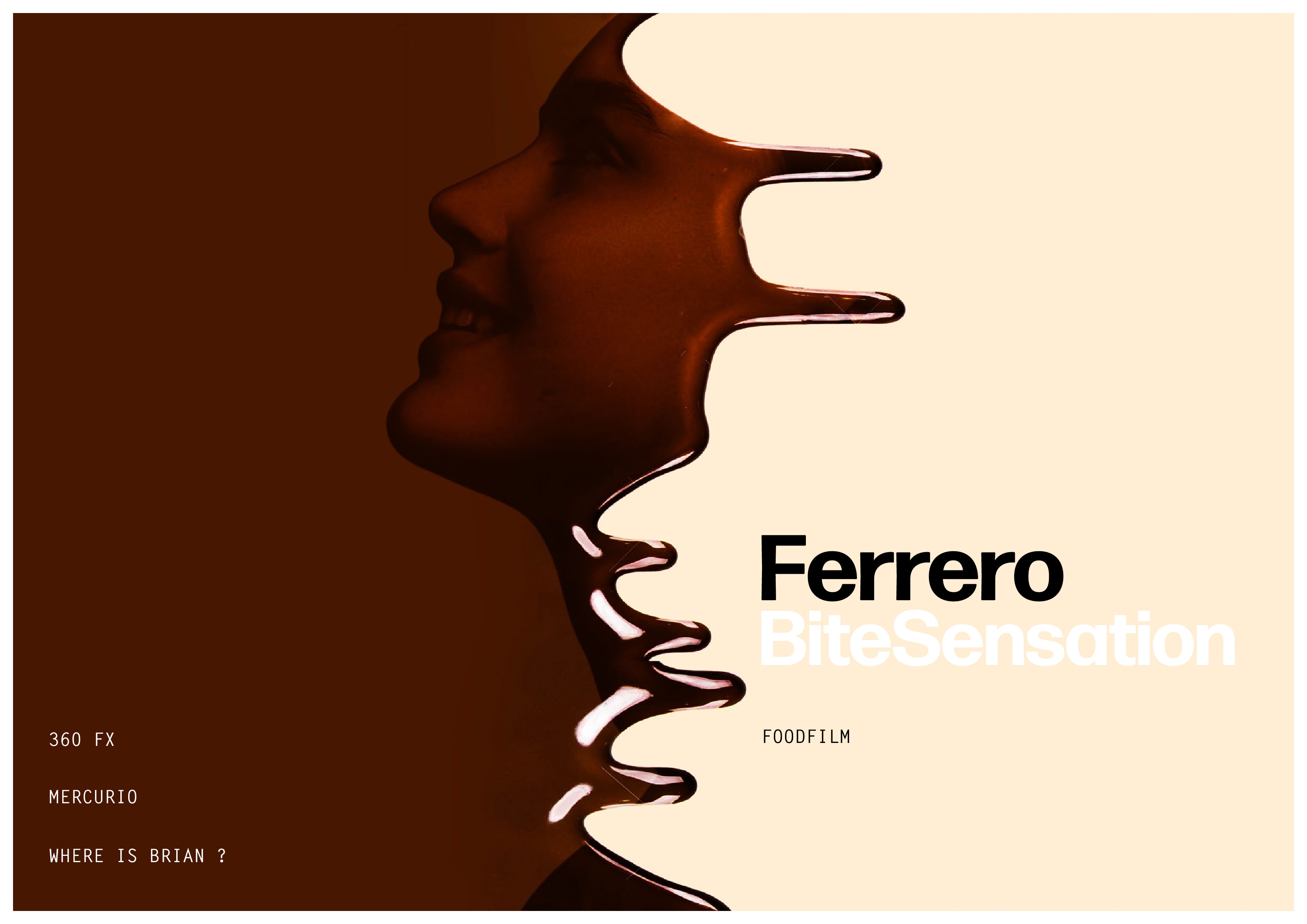

Making of:

How does a film treatment looks like,

when it’s made by Foodfilm ?

A “Scientific Analysis” of our work !

by Brigitte LUTRAND PEZANT,

Faculté des sciences & ingénierie,

anglais pour scientifiques.

Behind the Scene

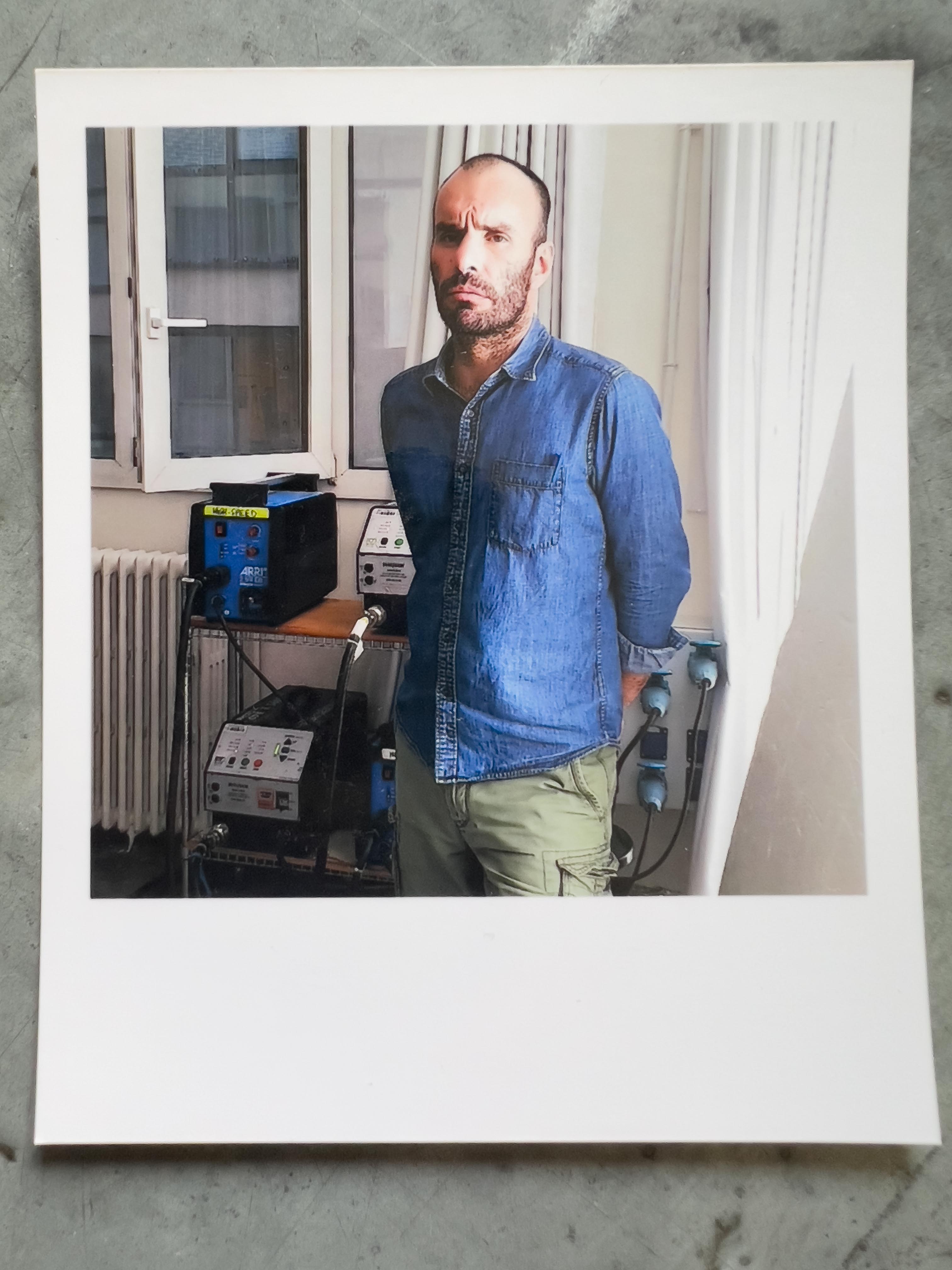

Michael Roulier

Phillippe Lhomme

Chris Hodgkiss - Young & Rubicam London

Emmanuel Turiot - Food Stylist

Eddy Marie - Food Stylist

The Foodfilm Team

Thomas Nagabbo

Pip Bishop

Jean Pierre Grandet

Thierry Pouffary (Phantom OP+DIT)

& Claire Gilbert (assistante)

How to avoid reflections